Previous Chapter 15 - Recruiting Next Chapter 17 - Patrolling

Chapter

16 – Training and Equipment

To

quote one of the most common statements encountered during the

collation of this chapter, “in the beginning the training was a

shambles and the equipment was rubbish”. Despite the initial

havoc the UDR was able to mount operational patrols on the day of

its formation, 1 April 1970.

The .303 Lee Enfield rifle was replaced with the NATO

standard 7.62 self-loading rifle (SLR) in late 1971. In the early

90s the Bull-Pup design SA80 replaced the SLR. By 1971 the Company

had also been issued with modern radio sets that were easy to

operate. Landrovers protected with macralon armour replaced the

soft-top Landrovers loaned to the Company. The Company also had a

Shorland armoured car. These armoured cars derived their name from

their origins. The firm, Short and Harland built it on a on a

Landrover chassis.

By 1974 the UDR had developed an all-round expertise and

were producing well-trained professional soldiers. Many UDR

Instructors spent many months away from Northern Ireland training

Regular Army units before they were posted to the Province. But

despite having the ability to operate beyond its limited tasking,

the UDR was always a “Political Football” and the role of the

UDR was never expanded and the majority of senior officers and

soldiers kept hitting the glass ceiling.

Occasionally large-scale operational patrols and searches

were planned and conducted by the Company with the usual

accompaniment of visiting officers in tow. They always posed

questions that could only rile the professional they were

addressing. “Well, Sergeant Major, how do you feel at being

allowed to mount this type of operation?” The usual conversation

killer was, “Sir, we should have been allowed to do this years

ago and more often”.

Basic

Training – 1970 Style

“That

early experience at Macosquin was quite unique. The British

government had disbanded our only defence against the IRA and we

were unsure as to what the UDR would be allowed to do. In those

early days the training was a shambles because there were

insufficient weapons to go around so we had to do our marching

drill with brush shafts. John Kerr was the main instructor at that

time.

Our training was far from professional when you compare it

to our later training. We did not know how to march and many people

were not at all familiar with the army weapons. As time went on the

standards did improve.

We had to report to Macosquin B Special hut every Sunday

morning, after that, until our basic training was completed.

I

knew quite a few of the men at Macosquin. In those early days we

were equipped with the .303 Lee Enfield rifle, the Sterling SMG and

some officers had pistols. We borrowed vehicles from other army

units when we wanted to go to Magilligan or Eglinton ranges for

live firing” S11.

Photo 36 On the Magilligan Ranges in 1970

“

In those early days we received very little training but as time

went on it improved. I remember well the second night I turned up

for training at Macosquin, I was given a rifle and ammunition and

told I was going on duty in Londonderry! We went there in a

soft-top 4 tonner; the late John Cochrane was driving with myself

and another soldier on rear guard. We stopped in Londonderry to

pick up two other personnel and then proceeded to set up a VCP on

the Letterkenny Road. As I hadn’t known that I was going on duty,

I had no food with me and I can remember trying to heat a tin of

Compo beans and sausages on the manifold of a Landrover” S

Brownlow.

“I

had been in the army cadets so I was familiar with a lot of the

military terminology. I hated marching but there was no great

demand for marching or drill in the UDR. I knew a lot of people in

the UDR but I did not feel comfortable when I first joined. I

preferred the operational duties to all the army formality.

My basic training was very basic. For example, there was a

shortage of radios for training purposes. The voice procedure

training consisted of one radio and the remainder of the class

using a matchbox or cigarette packet to simulate holding a

mouthpiece.

The training was good enough for what was expected of us on

the ground. All we were allowed to do in the early years was foot

patrols, searching vehicles and manning vehicle checkpoints. As

time went on we were given more advanced training and allowed to

carry out more demanding tasks while on patrol” S24.

“On

a Saturday I did my basic training. That included stripping and

assembling the Self Loading Rifle (SLR) and the Light Machine Gun (LMG).

After that we were examined on our weapon handling abilities with

the Test of Elementary Training (TOETs) and passed. After being in

the regular army and the TA for so long it took me a while to

adjust and accept the UDR approach to discipline.

Then on the Sunday night I was out on operational duty in

places like Swatragh and Kilrea. The basic training did not prepare

me for that experience. I picked up the tricks of the trade as I

went along. Learning how to conduct myself while out on patrol was

important for my survival” Ted Jamieson, 2006.

“The

initial training was limited and the real training was ‘on the

ground’ where I could watch and listen to my more experienced

buddies” S22.

“Our

radio equipment in the early days was of a low quality. The initial

issue was A41s, C42s and Pye Bantams and these were totally

unsuitable for the tasks we were performing. We were constantly out

of communication with each other” S4.

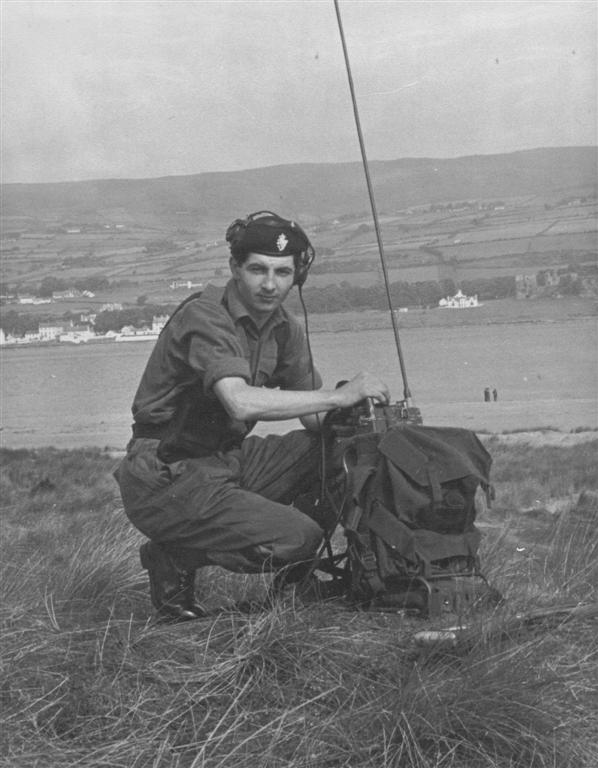

Photo

37 On the Magilligan Ranges with the A41 in 1970

“After

F Company’s first VCP the lack of weapons continued for about six

weeks and then the company was issued with ten rifles. We thought

this was great; however at that time F Company had about thirty or

forty members and ten rifles did not stretch far. So it was that

the rifles had to be signed out from one person to another. Some

men kept a rifle at home and they signed them out to other members

of the company.

One evening F Company set up a VCP on the main road, just

outside the village of Toome. They stopped the Prime Minister (NI)

James Chichester-Clarke who was on his way home. What the patrol

said to him on that occasion is not fit for reproduction. But they

did leave him in no doubt that the way they were being treated was

less than satisfactory. Two days later F Company had more rifles

than they could cope with. No doubt the meeting with James

Chichester-Clarke on the Toome road had the desired effect” S4.

“Very

soon after that we were called upon to attend a range meeting at

Eglinton Range. When I arrived at Eglinton Range I found a very

strange procedure in progress. Eventually it was my turn to be

called up to the firing point and fire ten rounds with a No 4 .303

rifle at a Figure 4 target, which never moved or never seemed to

have been marked.

When the next detail went on to the firing point, I went up

to the Firing Point Officer and said to him, “How did I get on

there?” He said, “What do you mean, How did you get on?” I

said, “I didn’t see anyone marking the target, I didn’t see

the targets being turned, I didn’t see the targets being patched

I would like to know what’s going on?” He replied, “You have

just passed your recruits training. The reason for you being here

is simply to ensure that you can safely handle the .303 rifle. You

have proved this. As for where your shots went on the target I have

no idea”. That was my recruit training in the Ulster Defence

Regiment” S4.

“One

night in Kilrea one of our Lance corporals, issued with a Sterling

SMG, managed to shoot out the windscreen of an army 1800cc car.

With the smoke still curling from the barrel of his gun he

demanded, “Who fired that shot?” S47

“Some

of the officers in the UDR had been commissioned without going up

through the ranks. When they went out on patrol they were very

naive and it became the Platoon Sergeants and the soldier’s

responsibility to educate them on patrol tactics. Luckily most of

these types of commissioned officers were eager to learn. Some were

not afraid to say, “Right boys, how do we go about this?”

“Keep me right, boys, keep me right.” They were not

prepared to simply learn from their mistakes, they wanted to

benefit from our experience. We had respect for that type of

officer” S24.

Basic

Training – 1974 Style

“Training

in E Company became highly professional as skills and drills were

perfected for all our operational tasks. We developed skills such

as covert vehicle and foot patrolling, first aid, signals,

anti-ambush drills, specialised search capabilities, helicopter

drills and intelligence gathering.” V Hamill, (2007)

The

first aid training days could be messy affairs. One of the Platoon

Sergeants was a butcher by trade and he would supply the

instructors with a bizarre assortment of animal guts, bones and

blood. This made the casualty simulations very convincing.

“We

reported to the Permanent Staff Instructor (PSI) at E Company the

Thursday after our initial kit issue. He was going to organize our

training, which would take four weekends plus four Thursday

evenings after which we would hopefully be sufficiently trained to

be allocated to a Platoon and then to be allowed out on operational

duties.

The training was intensive and whilst it concentrated on

weapon handling it covered many other subjects such as map reading,

first aid, field-craft, radio communications, yellow card rules on

engagement, and we were tested throughout the training programme.

Being competent at stripping and re-assembling a Self Loading Rifle

(SLR) in the dark or load twenty rounds of 7.62 ammunition into a

magazine in less than 15 seconds was difficult at the start but we

soon became very proficient.

Learning the phonetic alphabet was quite a task but

amazingly this has stuck with me to this day. Having passed the

basic training requirements we still had to carry out live firing

of our weapon before we would be allowed to do operational duties

and the PSI informed us that the following Sunday had been booked

as a Range Training Day at Magilligan Camp and we should report to

Laurel Hill for 8.00 a.m.

Sunday duly arrived and myself plus another seven recruits

reported for duty as ordered. The camp was busy because it was a

Company Training Day and there were about forty soldiers getting

ready to move out. We drew our weapons out of the armoury – each

soldier is issued with his own weapon – and we were given two

magazines but no ammunition. The eight of us got into two

Landrovers and the PSI had organized two armed escorts in the rear

of each vehicle with loaded weapons to accompany us to the range.

It was a beautiful Sunday morning as we travelled out the

Castlerock Road and along the coast road to Magilligan. On arrival

at the training ranges the PSI and his training staff took us to No

1 Range while the remainder of the company went to No 3 Range.

We spent the morning putting into practice the drills we had

learned in our training such as loading, unloading, make safe,

changing magazines and dealing with stoppages. Of course we were

not to know just how dirty a weapon gets after a day of live firing

and just how much effort is needed to clean it. It is a military

offence to put a dirty weapon back into the armoury as many a

soldier found out to his financial cost.

The main objective of the range day for us was to make sure

we were safe and competent in a live firing situation and to get

each of our weapons zeroed to our individual needs. In our training

we were taught the theory of aiming, holding and breathing and

grouping shots four inches above the white patch on the target at

100m. Making that happen took a lot of practice but we all got

there and one of the recruits could group his shots very closely

and it was obvious even on his first day at the range he was going

to be a very good shot. He eventually went on to represent the

Battalion on shooting competitions.

At the end of the range day we joined the main body of the

Company. The ranges all had to be cleared by collecting the empty

brass cases. The targets also had to be “patched up” and

returned to the Range Warden’s hut.

Once this task was completed the Company had to line up in

front of the Company Commander. We were ordered, “For inspection,

Port Arms, Show Clear!” The NCOs checked that all our weapons

were clear of live ammunition. Then as the NCOs checked our pouches

we shouted out the declaration, “I have no live rounds or empty

cases in my possession, Sir!”

It was only after that the soldiers loaded up their weapons

with magazines of live ammunition and we made our way back to

Laurel Hill.

What a day this had been. I had fired a couple of hundred

rounds, managed to get a reasonable group on the target and the PSI

informed me I was now cleared for operational duties. I was to

report to the 22 Platoon Commander to get my duty roster for the

coming month. That was the start of many operational and training

duties over the next 15 years” S39.

“We

adopted the catchphrase “work hard and play hard” especially at

annual camp which was the highlight of our training programme. Camp

was a break from operations but camps always had a serious training

purpose. We trained at camps in England and Scotland as well as at

Ballykinlar and got to know the training areas very well indeed at

Warcop, Wathgill, Otterburn, Barry Buddon, Thetford, Cameron

Barracks Inverness, and Folkestone.

Travelling to these camps was by means of commercial ferry

and coaches, sometimes by ‘Green Vehicles,’ on one occasion by

courtesy of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary in a Landing Ship Logistic

from Belfast to Liverpool and eventually by C130 Hercules aircraft

flying out of Ballykelly.

I’ll never forget the ‘day off’ we had one year at

Folkestone when the entire company took a trip by ferry across the

English Channel to Boulogne in France. We successfully managed to

get everyone back to camp at the end of a long enjoyable day after

several head counts by the Company Sergeant Major who by that stage

had had at least one sense of humour failure” (Hamill, 2007).

Sergeant McNeill one of the first PSI's

Permanent

Staff Instructor (PSI) Duties

“One

of the most interesting things that ever happened to me as a PSI

occurred about two years into the posting.

On

a Sunday morning I received a telephone call to go into E Company

lines because they were having an NCOs cadre and the Ammunition

Technical Officer (ATO) had failed to turn up or had indicated that

he was too busy to attend and give a lecture on explosives. Could I

fill in for him? Now I know very little about explosives but then

the people on the cadre would know less. I decided to go in and

give a lecture.

As I was about to start this hastily prepared lecture on

explosives George Lapsley appeared in the lecture room together

with the General Officer Commanding (GOC) and a whole entourage of

Staff officers and assistants who set themselves down in the back

row.

If the ground had opened and swallowed me it could not have

been worse. But Martin Luther said on one occasion, “Here I

stand, I can do no other may the Lord help me”. I was in that

position and understood how Luther must have felt when he nailed

his theses to the Wittenberg church door in the year 1517.

So I started. I have a fairly good memory for things that I

have read in books. To many this may seem irrevelant but I

remembered that Alfred Nobel was asked the question, “What is an

explosive?” It is a very simple question but a very difficult

question to answer. The answer to that question is, “An explosive

is any substance whether liquid or solid which can be transformed

from its liquid or solid state into a state of gas”.

After talking about high explosives, low explosives, how

explosives were formed and the danger from explosives and that

different types of gelignite deteriorate under adverse conditions.

I asked the class the question, “What is an explosive?” and I

had one or two half-hearted replies. Then I repeated Nobel’s

famous quotation.

After

the lecture was over the GOC came up to me and said, “That was

wonderful, how many courses have you done on explosives?”

Of course I had to admit that I had done no courses on

explosives and I was simply filling in for the ATO who was too busy

to attend and so that the cadre could proceed unhindered. I can

tell you it was not an experience I would like to repeat” S4.

Sandy

Baxter and the Ammo Boxes

Sandy

Baxter was one of the early volunteers for the UDR. One year at

annual camp on the Lydd & Hythe ranges Sandy was responsible

for issuing ammunition on one of the live firing ranges. This

ammunition was of inferior quality as it had either been on the

round trip to or else captured in the Falklands conflict. Sandy had

no incidents with the ammunition but became a victim of the

ammunition boxes themselves.

It was a bitterly cold day standing so close to the sea

front. Sandy used the empty ammo boxes to build himself a sentry

box to stand in and issue the ammunition from. He even used his

camouflaged Poncho (rain coat) to cover his little den.

As midday approached the driver of the four-ton lorry was

ordered to go back to base and collect the midday meal. Jimmy, a

very experienced driver who enjoyed driving holidays around the

European WW2 battlefields, reversed into the little den and Sandy

was buried under the ammo boxes with nothing hurt but his dignity.

Officer

Training – Sandhurst

“At

forty years of age I was sent to Sandhurst. Many people said,

“That’s the end of him. He will not survive.” I did. I made

up my lack of fitness and lack of youth with my experience. When we

went out on the night exercises all the young officers loaded

themselves down to the ground with bottles of minerals and crisps.

All these items added weight. When I got my rations I threw half of

them away and only took the bare necessities. I seemed to survive

on half rations much better than the young officers did, loaded

down with all sorts of luxuries” S4.

“I

had been promoted from Private to Lance Corporal as I had

previously expressed an interest in a Commission and had been

earmarked for Officer training. There were no Officer Cadets in the

Regiment at that time and I was frequently reminded that I had

better not put a foot wrong otherwise that would be the end of any

ambition I had to become an Officer.

In May 1971 I successfully attended an Officer Training Course and was appointed Second Lieutenant and posted back to E Company to assume command of 22 Platoon. By then the Company had grown to three Platoons. 21 Platoon was made up of men drawn roughly from the Portstewart and Portrush area. Twenty-two Platoon consisted of men from the east of Coleraine and 23 Platoon had men mainly from west of Coleraine” (Hamill, 2007).

Previous Chapter 15 - Recruiting Next Chapter 17 - Patrolling