Previous Chapter 1 - Irish History Next Chapter 3 - Standing Armies and Militias

Chapter

2 - Coleraine History

Naming

Coleraine

Coleraine

(Cuil Rathain) has been interpreted as either “the ferny

corner” or “the rath at the bend of the waters”. Either

interpretation suits the topography of Coleraine at the time.

Mullin (1998) has suggested that the rath referred to was probably

the earthen structure on which the Citadel was later built. This

feature was located where Hanover Place now stands.

Coleraine

Name Changes

County

Londonderry was originally known as O’Cahan’s land. In 1584 Sir

John Perrott the Lord Deputy relocated Coleraine town at

Drumtarsey, now called Killowen and then in 1585 all of

O’Cahan’s land, parts of Tyrone and Donegal became County

Coleraine.

The sloping ground of Drumtarsey and the sand bar at the

mouth of the River Bann made Coleraine unsuitable for a major town

location. Derry city had a better harbour facility and was then

selected as the major town. The county name was changed to

Londonderry in 1610. Coleraine town was then relocated in its

former position in County Antrim.

In 1610 the Londoners came to an agreement with Sir Randal

MacDonnell, the lord of County Antrim. Coleraine town, the

fisheries and an area with a three-mile radius around Coleraine on

the east side of the Bann became part of Co Londonderry. That

three-mile area was taken over and developed by The Honourable The

Irish Society itself. This new territory was known as The

Liberties.

Coleraine

Town Plan

The

plans for the layout of Coleraine town were drawn up by Sir John

Perrott and were similar to the plans for Londonderry city. The

Irish Society started building and developing Coleraine in 1610 and

good progress was reported up to the year 1611. By 1612 the

building programme was bedevilled with corruption and incompetence

as those tasked with developing the town spent most of their time

on stripping the countryside of the rich natural resources for

their own gain.

The fortifications of the town were five earthen ramparts

with the sixth side faced the River Bann. The ramparts were six

feet high and sixteen feet thick with twelve feet bulwarks inserted

at irregular intervals. The bulwarks were too narrow to be used as

artillery locations.

A

four-foot wide and four-foot deep trench was dug outside the

ramparts and in some places this was serviced by spring water to

create an obstacle. The total distance around the town defences was

2,000 yards. This measurement shows that Coleraine town and

defences were half the size of Derry.

A drawbridge and gate was placed at each of the two

entrances into the town. The King’s Gate was located at the end

of the main road where St Patrick’s church ground ends. The Blind

Gate was located centrally in the fourth rampart facing due south. The only remaining vestige of these 400-year-old

fortifications is the north rampart that drops down into Anderson

Park behind St Patrick’s church.

Construction of the town Citadel started in 1650. It was

supposed to look like a miniature castle with high walls and

ramparts. One of the few ever built in Ireland still exists in

Limerick. By 1662 the Coleraine Citadel was only 10 to 12 foot

high, the walls were unfinished and no ramparts had been added

(Kerrigan, p101). In 1670 it was referred to as ‘the late

demolished citadel’ (Mullin, p105).

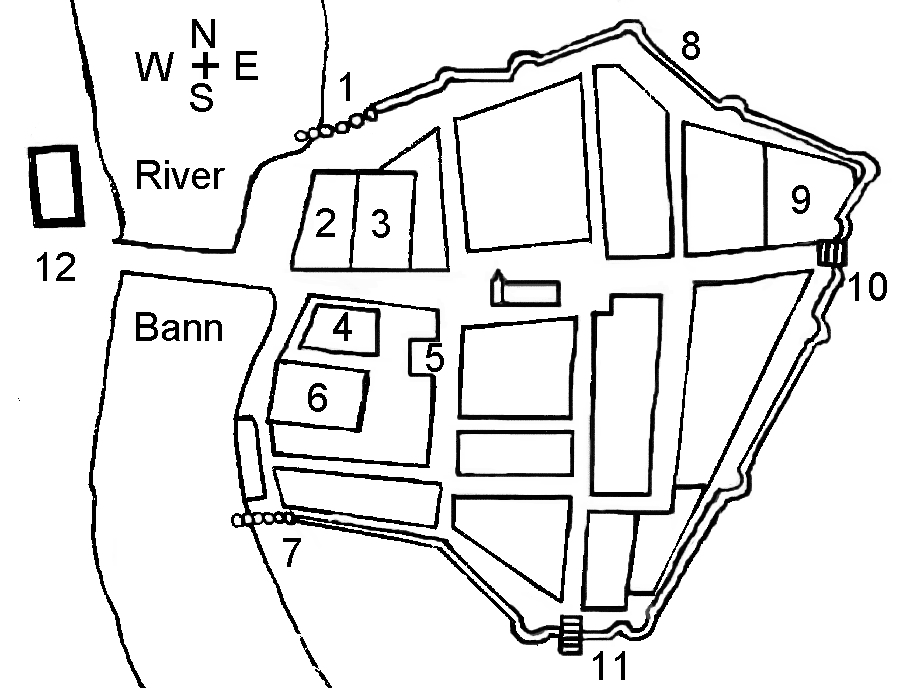

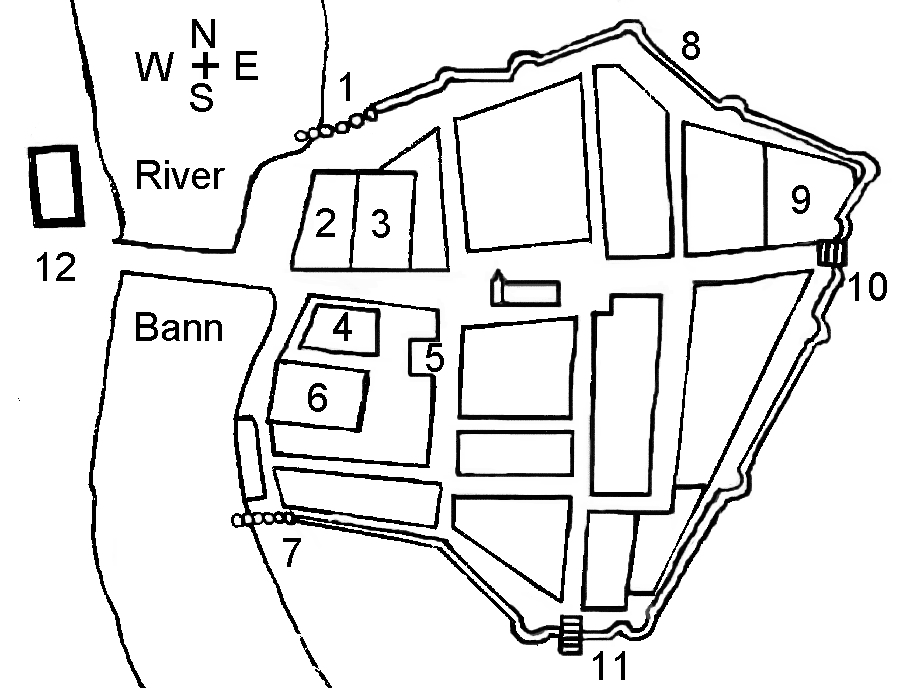

The

following map is a composite map showing the general layout of

Coleraine town as it evolved between 1609 and 1850.

Legend

North

Palisade

Customs

House

The

Barracks

The

Abbey (Dominican monastery)

The

Shambles (Meat Market)

The

Citadel

South

Palisade

North

Ramparts

St

Patrick’s Church

King’s

Gate and Drawbridge

Blind

Gate and Drawbridge

Drumtarsey

Castle

The

town remained fortified for 100 years until the early 1700s when

the town started to expand beyond the boundaries of the ramparts.

The town defences were never improved upon other than being

repaired and strengthened for the 1798 Rebellion.

The

Town Watch

The

townspeople were responsible for manning the town watch. The

records show that the watch was operating from October 1678 until

April 1706.

Mullin

(1979, p49) explains that in 1862 a superintendent and six watchmen

operating from 9pm until 4am in the summer and 6am in the winter.

Their main role was policing the town and fire watching. They were

stood down when the constabulary were established in Newmarket

Street in 1862.

The

Plantation of County Londonderry and Coleraine Town

County

Londonderry had to be settled differently from the other counties.

Planters and undertakers had been ignoring the county despite it

having the best land in Ulster. Their main concern was that Sir

Donnell, the O’Cahan chief, would be released from the Tower of

London and return with his ferocious clansmen to reclaim his lands

(Falls, p176). In the end the king demanded that the London

Companies should settle the county.

The

Londoners’ Plantation

When

the Plantation started many of the surviving native Irish lost

their land and were ordered,

“…to

depart with their goods and chattels at or before the first of May

next (1609) into what other part of the realm they pleased.”

(Joyce para 525).

County

Londonderry was then settled in what was known as The Londoners’

Plantation. The first grants were made to The Irish Society who was

directly responsible for developing both London-Derry and Coleraine

towns and the attached Liberties around both towns. The second

grant was made to the twelve London Livery companies who acted as

landlords.

The third grant of twenty-five percent of the land went to

the native Irish freeholders. Those who lost property in the

redistribution such as Sir Thomas Phillips and finally, the

Protestant Bishops were also granted land. Any map outlining this

allocation of land in Co. Londonderry is represented by a patchwork

of approximately 150 plots of land covering the whole county.

One

of the best-known Livery Companies was the Clothworkers. They were

granted the land on the west of the Bann where they were

responsible for building the Clothworker’s building at the end of

the Bann Bridge and developing the Killowen area.

The

Obligations of the Livery Companies

When

the Livery Companies were allocated their portions of land they had

to undertake certain obligations within the first three years to

settle people on their plots of land for its cultivation. The

Londoners failed to attract enough settlers to Ulster because the

confiscated territory was ten times larger than the initial

estimate. For that reason and counter to their obligations, many

settlers retained the native Irish on their lands to ensure it was

cultivated.

Those

allocated 2000 acres had to build a stone castle and surround it

with a stone enclosure (Bawn). One of these is still standing at

Movanagher near Kilrea. Those allocated 1500 acres had to build a

stone house and surround their immediate dwelling with a bawn.

Those allocated 1000 acres also had to surround their immediate

dwelling with a bawn.

Photo3.

Movanagher Bawn

Each

of the undertakers then had to bring in at least twenty-four

Scottish or English Protestant tenants to live on each 1,000 acres

allocated to them. They all had to be over the age of 18 years.

These tenants were expected to build their family homes close

together near the undertaker’s home so that there was a high

degree of mutual protection. In some cases there was no requirement

for the settlers to build their own homes.

“Irish

houses from which the owners were to be turned adrift should be

preserved for the use of the English settlers throughout……..”

(Hill, p367)

The

undertakers were further obliged to store and issue the arms

necessary for the defence of their plots and parade their tenants

every six months. This form of military service was similar to the

militias used in England.

Churches

and Abbeys

Many

churches, monasteries and abbeys in the Coleraine area have been

established and in turn plundered and destroyed during the town’s

turbulent history. The dominant religion of the Coleraine area in

its early history was the Celtic Christianity of St Patrick.

Starting in AD 1172, this faith was steadily replaced by Roman

Catholicism. When the Protestant Plantation started in 1610 the

parish churches of St Patrick’s and St John the Baptist

(Killowen) became Protestant churches.

St

Patrick’s Church

Legend

has it that Coleraine was given its name by St Patrick. This

happened in AD 432 when a local chieftain called Nadslua gave St

Patrick some ground on the east bank of the Bann to build his

monastery (O’Laverty, p161).

The grandson of Nadslua was to become the Bishop of

Coleraine.

The

monastery survived until 1213 when it was demolished along with all

other stone edifices in the town but the church survived. Thomas de

Galloway conducted this act of vandalism. It provided him with most

of the material he needed to build a castle on the west bank of the

Bann. There he destroyed the abbey founded by St Carbreus in 540

and built Coleraine castle on the foundations. The site was located

just behind the grounds of the County Hall. Coleraine Castle was

destroyed in 1221 and rebuilt in 1228. The church of St Patrick has

thrived well in the middle of the town ever since.

St

Mary’s Dominican Abbey

In

the mid 1200s the MacEvelins founded the Dominican monastery of St

Mary’s in Coleraine on the east bank of the Bann (Carlisle,

1810). It was located in the southern limits of the present Diamond

building. In 1556 the Dominicans abandoned St Mary’s and it was

granted to Sir James Hamilton. He transferred the ownership to Sir

Thomas Phillips in 1604.

When Sir Thomas Phillips was developing Coleraine town as a

private enterprise between 1605 and 1610, he fortified the abbey

and used it for his private accommodation (Mullin1976, p29).

Despite this interruption, St. Mary’s became the first university

in Coleraine when the Dominican Order assigned it that status in

the year 1644. The Dominican order may have been relocated in the

Coleraine area because the last known Dominican from St Mary’s

was called Father JD Cunningham who died in1843 (Coleman 1902, in

Mullan & Donnelly, 1992, p93).

Killowen

Church and Maconachie Hall

The

name Killowen dates back to 1607 and it is derived from a

misinterpretation of the Irish ‘Kill Eoghain’ or the Church of

St Eugene. Before that date the area was known as Drumtarsey,

‘the ridge on the other side’.

The

Roman Catholic Church of St Eugene, later called St John the

Baptist (1609) was situated within the northern boundary of the

present Killowen graveyard. It was built in 1248 by the

Anglo-Normans to be used by the soldiers garrisoned at Drumtarsey

Castle as well as the settlers of Drumtarsey (Machonachie, p6).

Photo

4 Killowen Church, St Johns and Maconachie Hall

At

the start of the Plantation the Protestant settlers confiscated the

church. It was restored in 1616 and renovated in 1690 and 1767.

Also at the start of the Plantation, the Roman Catholic faith was

outlawed to the extent that the Protestant Bishops inherited their

land and no Roman Catholics or mere (pure) Irish were permitted to

reside in Coleraine town. That restriction zone extended from the

Irish Houses on the northwest side of the town at the top of the

Cart Haul (Carthall) road, Laurel Hill on the south and Spittal

Hill on the east (MacLaughlin, p8). Every day before sunset, all

Roman Catholics and the mere Irish still inside the restricted zone

were warned to leave the town by the ringing of the Curfew Bell.

Location of the Curfew Bell

The

James O’Hagan map (1845) refers to the location as the Old Church

and then the Valuation Map (1858) refers to the location as the

Parochial House.

The present Protestant church at Killowen was then built in

1830. After that date the origional Roman Catholic church was used

as a parochial school until the new school was built in Shuttle

Hill. The old Roman Catholic church then became known as the

Parochial Hall.

Martha

Gamble was born in 1922 and recalls, ‘My mother died when I was

three years old and I had to go and live with my grandmother on

Kyle’s Brae in the house beside the upper chapel gate. The

Reverend Abbot would visit my grandmother once every three months

and give her £3 from the Protestant Orphan’s Fund. She would

fold up a towel for him to kneel on when we prayed together. In

1927 I started school at the Killowen Public Elementary school. We

had to bring our own aluminium cups to school with us and for the

break we would go to the Parochial Hall for a cup of cocoa. Mrs

McKay from Strand Terrace was there to ladle the cocoa out from a

big boiler and I remember there was a photo of the Reverend Giles

hanging on the wall’.

In

1938 the Ministry of Education School was built directly across the

road. The Elementary School is now Killowen Orange Hall. The

Parochial Hall remained in use until it was demolished in 1961 and

Maconachie Hall was built on the foundations.

The

Mass Walk and St Johns

The

Roman Catholic parishioners displaced from St Eugene’s during the

Protestant plantation started to attend open air mass on ‘The

Mass Walk’ in the Somerset demesne lands (pronounced demean,

meaning owned by a lord) (Mullan & Donnelly, p140). This was

located on the Garrett Screen Road opposite the present Greenmount

Estate.

In the mid-18th Century the Roman Catholic

population of Coleraine town started to increase. Many native Irish

came to the town from the Limavady hills and Co Donegal; the places

their ancestors had been banished to in the early years of the

plantation (Mullan & Donnelly, p 155).

In 1760 the Wayside Chapel was built close to the Mass Walk

at Burnside. It had a thatched roof and was 50 feet long and 14

feet wide. At that time many Roman Catholics continued to exercise

their right to be buried in the Protestant Graveyard (MacLaughlin,

p6) where their Roman Catholic ancestors were buried.

The Wayside Chapel was vacated when the new Roman Catholic

Church was built in 1806. This building was unsafe and had to be

demolished. The present Roman Catholic Church of St John the

Evangelist, Killowen, replaced it. By the year 1835 it was almost

complete but another 20 years would pass before a wooden floor

replaced the earthen floor.

The Wayside Chapel was then converted into four labourers’

cottages. One of the last occupants was a character called

Constable Hemmingway. All that remains of the Wayside Chapel today

is the base of the north wall close to the modern cottage that was

built inside the old foundations.

Photo

5. Former Location of the Wayside Chapel

Castles

Coleraine

Castle

In

1213 Thomas de Galloway dismantled the Abbey of St Carbreus and

erected Coleraine Castle on the same ground (Lewis, p18). The

castle was destroyed in 1221 by Hugh de Lacy and Hugh O’Neill and

was then rebuilt in 1228 (Mullin p13).

When King James I granted a lease for the property to the

Clothworker’s Company in 1609 there was a cottage located on the

castle foundations. Later on William Jackson demolished the cottage

and built Jackson Hall. It finally became known as the Manor House

and was demolished to form part of the car park at the rear of the

County Hall.

Drumtarsey

Castle

There

was only one castle located in Coleraine town at the time of the

Plantation, Drumtarsey Castle. This castle and the first Bann

Bridge were built in 1248 by the Anglo-Normans. Both were located

close to the present Clothworker’s Bridge. O’Neill rebuilt

Drumtarsey castle in 1564 and it was still there in a ruined state

in 1608 (Mullin, p27). In 1619 Sir Robert McClelland built a castle

of lime and stone behind the present location of the

Clothworker’s building. It was 54 feet long, 34 feet wide and 28

feet high.

Bridge Street, Bridge and Captain Street in the distance. Drumtarsey Castle was located behind the large building at the far side of the bridge on the right.

Artefacts

Two

artefacts presented to Coleraine Corporation by the Honourable The

Irish Society have survived Coleraines tumultuous past, the Sword

and the Mace.

The

Sword

Andrea

Ferrara was a legendary sword smith from Spain. He was forced to

flee to Scotland during the reign of James V after murdering one of

his apprentices for spying on his manufacturing processes.

He established himself in Scotland as a sword smith and his

Basket Hilt Broadsword as well as his Claymore (great sword) became

known as a ‘Ferrara’.

On 27 July 1616 Alderman Probyn and Mathias Springham were

visiting the town on The Irish Society’s business when they

presented the Corporation of Coleraine with a Ferrara. This was a

gilded double-edged weapon with an overall length of 48 inches. The

makers name and mark are engraved on the blade. The scabbard is

still intact and is covered with crimson velvet. It has survived

intact to the present day even though it has been reputed to have

the flexibility of all Ferrara swords in that the blade can be bent

until the tip touches the hilt.

The

Mace

Eighty-six

years later, during the reign of Queen Anne in 1702, the Irish

Society presented the Corporation of Coleraine with a ceremonial

mace. The head bears the Royal Arms and the side has a harp

surmounted by the crown, shamrock, thistle and rose and the

initials AR (Anne Regina).

There

are also two inscriptions on the mace. The first one states,

“This

mace was given to the Corporation of Coleraine in the year 1702 by

the honourable the trustees appointed by Act of Parliament made in

Scotland for ye sale of ye forfeited and other estates and

interests in Ireland”.

The

second inscription is more recent and states,

“To

commemorate the signing of the Peace, 28 June 1919 after the Great

War, 1914–1918, this mace was gilded at the cost of the Hon. The

Irish Society, Sir Alfred J Newton, Bart, Governor”.

Previous Chapter 1 - Irish History Next Chapter 3 - Standing Armies and Militias