Chapter

5 - Military Tradition and the New Militias

The

Tradition of Military Service

After 1850 many Coleraine volunteers

continued to serve the Crown during Britain’s conflicts. That

included the Crimean War in 1855. After the Crimean War a Russian

cannon was presented to the town in 1859 to mark the contribution

made by the Coleraine volunteers. Coleraine volunteers were also

well represented during the Zulu War in 1879, the Egypt War in

1882, the first Boer War 1881 and the second Boer War in

1899-1902.

One of the local veterans, William McSheffery, called the

Boer Wars the first and second African wars. He served in both

and was invalided out of the Inniskilling Fusiliers at the start

of WWI before going on to dig the trenches in France. He often

recalled how he had to cut his spade through the bodies of men

and horses so that the trench followed the plans they were

working to.

Robert Gamble also fought in South Africa and his South

Africa 1902 medal has the clasps for the Transvaal and the Orange

Free State. He also served during WWI in the Royal Inniskilling

Fusiliers. He was too old for military service when WWII started

but two of his sons, Tom and Willie, joined 6 LAA Battery as

gunners while Robert joined 1st Airborne Division as a

paratrooper and Jim joined the pathfinders of the 1st

Airborne Division, the 21st Independent Parachute

Company.

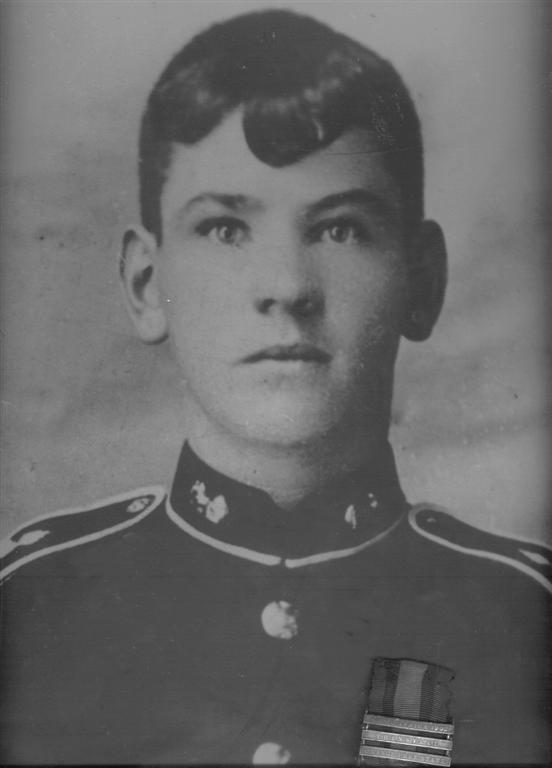

Photo 7 Robert Gamble and Photo 8 William Gamble

The

Ulster Volunteer Force

Just before WWI an illegal citizens’

militia was raised in 1911. It was used to preserve the

Protestant tradition and population in Ulster.

That militia was called the Ulster Volunteer Force and 300

volunteers were raised in Coleraine to oppose the implementation

of the Home Rule Bill. This Bill was introduced in 1886, 1893 and

then again in 1912. Its aim was to give Ireland a devolved

assembly with limited powers. Protestants opposed the Bill

because they would become a minority in the whole of a Catholic

Ireland.

Bonar Law, the son of a Portrush minister, became the

leader of the Conservative Government in 1911 and championed the

Ulster Protestant cause at that time. By 23 September 1911 there

were thousands of Orangemen parading in Craig’s grounds in Co

Tyrone. This was followed province wide by the Orange Order

providing the halls and facilities to train more volunteers who

were in opposition to the Home Rule Bill.

At that time a law was unearthed that stated two Justices

of the Peace could authorize military exercises in their

jurisdictions in order to provide an efficient citizens’ army

(Stewart, 1966, p69). Licences were duly issued and by January

1913 the Ulster Volunteer Force was 90,000 strong. The south

responded by raising a Catholic army of 190,000 Irish Volunteers.

The Coleraine UVF contingent was under the command of

Major JAWO Torrens. The drill instructors were Willie McGrotty

from Killowen and James Thompson (Mullin, 1979 p26). But with WWI

starting, the implementation of the Home Rule Bill was delayed.

The loyal volunteers joined the 36th (Ulster) Division

and went off to war. Drill Instructor Willie McGrotty from

Killowen was too old for WWI but his sixteen-year-old son, also

called William, forged his age and joined up.

The Irish Volunteers enrolled in the 10th

(Irish) and the 16th (Irish) Divisions.

Partition

The final Home Rule Bill had been

introduced in December 1920 and in December 1921 Ireland was

partitioned into the six counties of Ulster and the twenty-six

counties of the Irish Free State, each with their own

parliaments. Not only did the Irish lose six counties, the

British Army lost six Irish Regiments when they were disbanded.

On 12 June 1922 in St Georges Hall at Windsor Castle King George

V received the twenty Colours of the five infantry Regiments and

the Regimental Engraving of the South Irish Horse. He said,

‘I pledge my word that, within these

ancient and historic walls, your colours will be treasured,

honoured and protected as hallowed memorials of glorious deeds of

brave and loyal Regiments’.

Institutionalised

Discrimination

Institutionalised

discrimination throughout Ireland reached new heights after this

grossly unjust partition. The political structures in both new

states had an inherent sectarian bias. A Protestant Parliment for

a Protestant people and a Catholic Nation for De Valera were the

mutual calls.

The

border became an impassable barrier to the respective governments

wishing to alleviate the suffering of their isolated minorities.

The Irish government tried boycotting goods manufactured in

Belfast to coerce the Northern Ireland government to protect the

northern Catholics who were subject to discrimination and

murderous attacks, particularly in the Belfast area. The boycott

was of little value.

The

Southern Protestant Decline

Between

1922 and the mid 60s the downward spiral of the Protestant

population in the Republic of Ireland accelerated. From the

census in 1911 to the present the overall decline has been 68 per

cent (Hussey, p379).

There have been many reasons suggested for this decline

including an ageing minority, a prolific majority, anxiety,

assassination, mass departure and institutionalised

discrimination. The Central Statistics Office (2000, p55) states

that the Protestant decline can be attributed to the older

generation of the Church of Ireland and the Presbyterians as well

as the high birth rate and low mortality rates of the Roman

Catholics relative to the Protestant minority.

Kenny (2000, p92-93) has discussed how Protestants in the

Republic of Ireland were faced with an uncertain future in those

early years and that may account for them having the lowest rate

of fertility in Europe at that time. The Protestant clergy went

as far as to send a delegation to Michael Collins who reassured

them that the Protestants were welcome in the south. That

reassurance had little value because soon after that Collins paid

the price for signing the documents that divided Ireland with his

own life.

But the problem was initially compounded through

institutionalised discrimination, such as the protocol to be

followed after a mixed marriage. In the old Irish Catholic

tradition all female children were raised in their mother’s

religion and all the male children were raised in the father’s

religion. The Papal decree of Ne Temere was then used from 1908

until 1966. It ensured that when a Protestant married a Roman

Catholic, the Protestant signed a document stating that all their

children would be raised as Roman Catholics.

The Protestant decline in the Republic of Ireland was also

accelerated through exodus. In 1922 the big houses of the

Protestant landowners were being burnt and the working class

Protestants were being shot. For example, in April 1922 twelve

Protestants in Dunmanway, West Cork were picked out and shot in a

single day.

The

Ulster Special Constabulary

The

citizens’ militia had to be raised again in 1920 to counter the

murderous incursions of the IRA from the Republic of Ireland and

the equally murderous activities of the IRA in Northern Ireland.

The government called this citizens’ militia the Ulster Special

Constabulary (USC) and armed them with the 1914 consignment of

Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) weapons. The Ulster Special

Constabulary was formed as part of the Royal Irish Constabulary

and pre-dated the creation of the state of Northern Ireland.

(Doherty, 2007) As in 1913 when the UVF were training the local

Orange halls throughout the Province were used as training halls

by the USC.

There were three grades of special constable, the A

Specials who were full-time reserve police, the B Specials who

were part part-time police and expected to parade on one or two

nights each week for a four-hour duty. (Howard Gribbon was the

first commander of the B Specials in Coleraine)

The

C Special’s were available for emergency call-out and each man

had to provide his own personal weapon. The A and C Specials were

disbanded in 1926.

WWII

and The Coleraine Garrison

Coleraine

town did not have an army unit garrisoned from 1850 until the

British army raised 6 Light Anti Aircraft Battery, 9th

Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery (Supplementary Reserve) on

1 April 1939. The Battery was raised to counter the threat

offered by the German air force, the Luftwaffe. One of the

earliest volunteers was Jim Murray from Maghera who joined in

March 1939. The following month he attended a Bofors gun Anti

Aircraft course at Biggin Hill near London along with Robin

Martin from Coleraine and Stanley McQuigg from Macfin.

When 6 LAA Battery left Coleraine on 28 November 1939 to

take their part in WWII the Calf Lane Camp and the surrounding

towns were used to garrison many of the troops passing through

Coleraine on their way to the European battlefields.

On 26 March 1942, the Coleraine Battery was deployed for

Anti Aircraft defence of the Halfa Railhead in the Western

Desert. They used 20mm Breda guns captured from the Italian Army

for this task. The guns were mounted on three-ton trucks. These

were then loaded on the railway wagons of the train they were

protecting. On 2 April that year, Sergeant Jim Murray was wounded

twice on the left arm by ricocheting bullets as his gun crew shot

down a German Bf109 (Gamble, p73). Jim Murray was wounded again

in 1958 as he defended Swatragh RUC station from an IRA attack.

Photo

9 Railway Anti-Aircraft Protection In the Western Desert 1942

Ulster

Home Guard

Although

the English regular militias were raised again in Great Britain

on 27 May 1940 as the Local Defence Volunteers (LDVs), the 13,000

strong B Specials were expected to carry out the same role as the

LDVs as well as their normal duties in Northern Ireland. But on

29 May a new category of B Specials was created, the Local

Defence category. By 21 June the Local Defence category strength

was 18,742. The final title change took place on 24 August when

they became known as the Ulster Home Guard section of the Ulster

Special Constabulary.

The dress code also went through three phases. Initially

they wore civilian dress with an armband. Next it was black denim

battle dress and finally they were dressed in khaki battle dress

(Hezlet, p141).

“I

joined the Boveedy detachment of the Local Defence Volunteers in

1942. At the start of the war both the Ulster Home Guard and the

B Specials were dressed identically except for the shoulder

flashes or patches. Instead of having a shoulder flash with the

Ulster Home Guard on it the B Specials had a patch on the upper

arm with a B on it.

Many people were in both the Ulster Home Guard and the Bs.

If they were not required for one unit they paraded for the other

unit. There were also A Specials who volunteered from Garvagh and

they were posted out to guard RUC stations in Belfast and other

locations.

The Ulster Home Guard spent most of their time

training for land warfare. We did not become involved in

roadblocks; the Bs did that all the time.

The Ulster Home Guard was eventually stood down in 1944.

The photograph shows the Garvagh Ulster Home Guard Band outside

the Presbyterian Hall in Garvagh. They borrowed the pipes and

drums from Garvagh Pipe Band and marched at the head of the

Coleraine parade for the stand down of the Ulster Home Guard”

S7 & 8.

Photo

10 Garvagh Detachment of the Ulster Home Guard 1944

Operation

Harvest

Between

the years 1956 and 1962 the IRA mounted a terrorist campaign

called Operation Harvest. That campaign failed for many reasons.

The main reason was the fact that the Republic of Ireland did not

support the IRA. The Irish Government introduced internment and

used no jury military tribunals to deal with IRA prisoners.

Without political control and direction the military campaign was

undermined and the IRA was unable to galvanise support from the

nationalists community in Northern Ireland.

Many of the IRA s military operations were undermined by a

combination of information supplied to the RUC by a small MI5

unit, co-operation with the Gardi and with the B Specials out on

the ground every night restricting IRA activity. Davy Watton of

Coleraine had served in the Western Desert as a dispatch rider in

the Royal Engineers joined the B Specials on his return to

Coleraine. He was instrumental in the capture of two IRA men who

were preparing a set of plans and sketches of Coleraine Bann

Bridge.

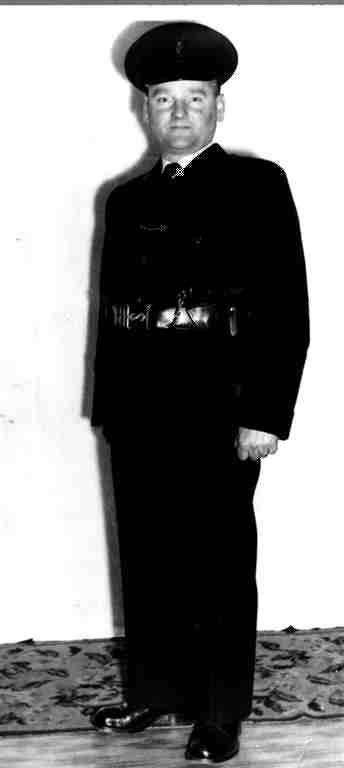

Photo

11 S/Constable Davy Watton

The

B Specials

“I

first joined the Knockloughrim Platoon of B Specials in 1953.

The platoon consisted of three sections. Each section had

a Sergeant in charge and six constables. The Sergeant was

normally promoted to the post because they had prior service in

the armed forces. Our wages were 50p a month or £6 a year.”

S9.

Training

“On

a drill night all you had to do was put your rifle over your

shoulder, get on your bicycle and ride into the local drill hall.

You were relatively safe from attack by Republican gunmen because

while you were on a training night your area was well covered by

other B Special patrols” S7 & 8.

“My

section drilled in Knockloughrim Orange Hall. Frank Pancott and

John Kerr were our Sergeant Instructors. Their job was to travel

around north Derry and train the B Specials on their drill

nights.

On

some training nights we had live firing practice in the hall. We

used the .303 Lee Enfield rifle fitted with a Morris Tube. That

was a sleeve barrel that allowed the rifle to take a .22 round.

On drill nights we always had two men posted outside the

hall with loaded weapons for our security. One man was posted to

each end of the hall. One night Davy Gamble was posted outside on

guard duty. He always carried a Sten Sub Machine gun. After his

stint of guard duty Davy came back into the hall and forgot to

unload the Sten. He dropped the Sten and we all jumped up onto

chairs as the gun started spinning on the ground and firing away

until the magazine was empty. Luckily there were no injuries.

There were shooting competitions nearly every Saturday.

This involved the entire local B Special Platoons. That included

Tobermore, Knockloughrim, Aughagaskin, Bellaghy and Garvagh. The

competitions were held at The Grange, Moneydig or Magherafelt”

S9.

Patrolling

“The

B Specials patrol operated for a four-hour shift. The first shift

was from 8pm to midnight and the second shift ran from midnight

until 4am. The third shift from 4am to 8am was rarely called for.

This four hour evening duty did not have an adverse effect on

your ability to do your normal civilian job the next day.

In the Garvagh area the Bs patrol consisted of a section

of one Sergeant and six men. At the roadblocks there were two

sentries at each end and the Sergeant with his two cover men in

the centre. It was

the Sergeants task to interview anyone stopped by the patrol.

Usually the patrols were transported to each roadblock by

a truck driven by a RUC officer. On other occasions the patrols

were delivered by a couple of the patrol using their own private

vehicles. The vehicles would be concealed and the patrol

conducted in a circular route to bring you back to the vehicles

again.

There were so many Specials out on patrol, it did not

matter where you tried to go, and inevitably you would run into

another Specials patrol. This would happen not once but many

times in the one journey. This was at a time when there were

fewer vehicles on the road, but believe me, you did not travel

far at night without meeting a Specials’ patrol.

The only thing that kept us from stopping traffic was the

fog or icy conditions. That was for safety reasons. The traffic

would be moving slowly in these conditions anyway so we could

identify the vehicle and driver easily” S7 & 8.

Local

Knowledge

“In

the Bs you relied on our local knowledge and prided ourselves on

our grasp of the local knowledge. If you were to take a B Special

to an area outside his local area, he lost that edge.

In

the Garvagh detachment we had a man in our patrol who was lost if

you took him to the end of his own road. One night we totally

befuddled him while we were out on patrol. Sitting in the back of

a covered lorry to be moved around our patrol area could be very

disorientating. When

the patrol was over we had convinced this man that we were

totally lost. We stopped the lorry and told him to get out and

inquire at the nearest house as to where we were. He knocked on

the door and his sister opened it. We had taken him back to his

own home” S7 & 8.

Equipment

“We

were issued with poor quality torches. In the early 1950s these

items were difficult to work with.

All

the time I was involved in the B Specials I did not see any

action personally. There may have been a bit of hassle on the

roadblocks at times but it never amounted to anything serious”

S 9.

The

Swatragh Attack

On

14 January 1958 at 10pm Swatragh RUC station came

under attack from a 70 strong IRA murder gang. These individuals

had chopped down trees to block the eleven approach roads into

Swatragh (Hezlet, p184).

That night the regular RUC in Swatragh had the added

protection of six B Specials from Upperlands. One team of the B

men were posted to the sandbagged position in front of the

station and the remainder were posted to a similar position close

to the Garvagh Road. On hearing distant explosions the road party

moved towards the RUC station and that was when the IRA started

their attack.

S/Constable Jim Murray was the first casualty with an eye

and a leg wound to add to the arm wound he received in the

Western Desert in 1942 (Gamble, 2006). Jim fired his Sten gun

until it jammed and the blood from the eye wound stopped him from

clearing the jam. At that stage S/Sergeant Thomas McCaughey

cleared the gun and with covering fire from the RUC Bren gun in

the upper floor of the station the terrorists were routed (Clark,

p108).

The sound of the gunfight alerted B Specials from the

neighbouring areas who closed in on Swatragh in their private

cars. They detained a well-known IRA suspect at one roadblock. He

had a bullet wound to his chin.

S/Sergeant Thomas McCaughey and S/Constable Jim Murray

were awarded the British Empire Medal for their bravery that

evening.

The photo shows Private Thomas McCaughey, E Company 5 UDR

on the right during a tea break on the Magilligan ranges in 1970.

The soldier in the back of the van is the late Bobby Boyd from

the Quartermaster’s Department based in Battalion Headquarters.

On 18 November 1985 Republican gunmen murdered Bobby

at his front door as he returned home from work. One of his

neighbours was convicted for supplying the information that led

to his murder.

Photo

12 Bobby Boyd and

Thomas McCaughey BEM

The

Ulster Defence Regiment vs. The B Specials

“When

you compare the achievements of the B Specials and the UDR I

believe the Bs were a more effective force in dealing with the

IRA. Because we operated in our own hometown, we knew everyone we

met and recognised his or her vehicle before it reached our

patrol. With the same token it was easy to identify strangers.

The UDR patrols were better equipped to deal with the

terrorist threat. For example, they had great radio

communications and night viewing aids.

Because the UDR units were more centralised there was more

time lost in preparing for patrols. The amount of time lost in

many operations was 25 per cent of the time available. For

example, the soldier had to report to a base depot in order to

draw his weapon, be briefed and then transported to the task

area. Then there was time lost on the return journey to stand

down.

In the Bs you were on fifteen minutes notice to grab your

rifle and make it to the designated point for the patrol.

Everything you needed for the patrol was in your own home.

The

general public had a better regard for the B Specials. Many

people regarded the B Specials as ruthless. The fact was that the

B Specials either stopped or deterred many terrorist actions. We

also stopped a lot of other criminal activity around the province

by being on the ground all the time.

At one time we had permission to shoot at any vehicle that

went through our roadblock without stopping. The threat was

always there and the general public did not take a chance on

running from a B Special patrol.

The UDR were issued with superior weapon systems but by

the time legislation had introduced Green, Yellow and Blue cards

you might as well have left your weapons in the armoury for all

the use or threat they presented to the terrorist” S 9.

The

B Special Criticism Answered

The

B Specials were neither equipped nor trained to deal with the

modern terrorist and the sophisticated equipment they used. By

1976 all the criticisms directed at the UDR by some B Specials

became history. The UDR were now on the ground every hour of the

day conducting large-scale patrol operations with the equipment

and training necessary to cope with the modern terrorist.

Previous Chapter 4 - Coleraine Garrison and the Rebellions Next Chapter 6 - The First Officer Commanding E Company