Previous Chapter 7 - Prelude to Terrorism Next Chapter 9 - E Company - The Middle Years - the 80s

Chapter

8 – E Company - The Early Years (1970s)

Attrition

The

British government started to wear down the terrorists in 1971

with the catchphrase, ‘An acceptable level of violence’. It

would be another six years before the IRA started their war of

attrition by adopting the principle of ‘The Long War’.

The

catchphrase, ‘An acceptable level of violence’ was first

coined by Reginald Maudling in December 1971 and repeated by

others such as William Whitelaw many years down the line. They

upstaged the Republican murder strategy from the onset. That

catchphrase expressed the mind-set of the British government.

They were prepared to accept a certain level of violence from

the IRA. That undermined the value of violence as a tactical

weapon.

The

IRA’s ‘Cutting Edge’ Philosophy

The

IRA’s murder campaign was designed to influence world

opinion, wear down British resolve and maintain a limited

Loyalist terrorist backlash. The IRA plan was not designed to

coerce the people of Northern Ireland into a United Ireland; it

was indirectly trying to coerce the British government into

uniting Ireland. This was the ‘cutting edge’ philosophy of

Adams in application, the Armalite forcing the political

demands. The whole community of Northern Ireland were hostages,

held to ransom by the IRA and murdered by them at the rate of

two each week. They were showing the world that Northern

Ireland was a failed democracy and political changes had to

take place. The IRA leadership was saying to the British

government, “We have not gone away you know. Start

legislating for our United Ireland and we will stop killing”.

The IRA leadership had the capacity to increase the

killing rate but they were on a ‘knife-edge’. An increase

in the killing rate would have resulted in a civil war that

nobody would have won. IRA violence failed to wrest major

concessions from the British government because they were also

on a ‘knife- edge’.

Although the British government showed scant regard for

the Unionist politicians, the first Ulster Workers Council

strike in 1974 delineated the line they could not cross without

raising Unionist and Loyalist wrath.

The IRA activist always went to ground until the

Loyalist ‘tit-for-tat’ attacks were taken out on the

general Roman Catholic population. These Loyalist sectarian

attacks promoted the idea that the Roman Catholic community

needed the protection of the IRA. That way, the whole

population of Northern Ireland were hostages to all the ‘mad

dogs’ of Irish politics for the next thirty years.

In these early years the symbiotic relationship between

politics and murder cut away the middle ground and polarised

Northern Ireland society. There was a continual movement of the

population and the former ghettos were transformed into

enclaves controlled by terrorists.

Internment

9 August 1971

“If

ever there was validity in the term ‘a pivotal moment’ this

was it. Unrest and civil disturbances had reached intolerable

levels and political uncertainty coupled with pressure from

Westminster and Dublin was not helping. We all felt something

had to be done and while we were still in a relatively

embryonic state in terms of our operational status and

capabilities, nevertheless we were willing to do whatever was

necessary to help bring peace, stability and normality to our

daily lives.

Most

of us thought events were going downhill so fast there would be

civil war which would probably be very bloody but short lived

and then we could get on with the rest of our lives. How wrong

we were. We were only at the beginning of what was to become

‘the long war’ and none of us ever dreamt at that time that

it would take another 30 plus years of terrible violence before

we could see an end.

In

the early hours of 9 August 1971 the RUC and Army carried out

arrest operations of suspected IRA men across the Province,

which led to the introduction of internment. Most of these

arrests were carried out while the suspects were still in bed

and involved breaking down the doors of many of the houses

where the suspects were sleeping. This naturally provoked the

families and caused immense resentment in entire communities

especially as the suspects were then taken away to face harsh

questioning and detention without trial. The violence on the

streets, which followed these arrests, was immense and

widespread. Even more important was the impact and loss of face

suffered by the Official IRA. Although we did not realise it at

the time, nor did we fully appreciate the leadership struggle

and dissention, which was going on in the ranks of the IRA, the

net result of all these events led to hundreds of Republicans

joining the Provisional IRA. By the end of 1971 the Provisional

IRA had not only grown in strength immensely but had also

acquired substantial quantities of weaponry.

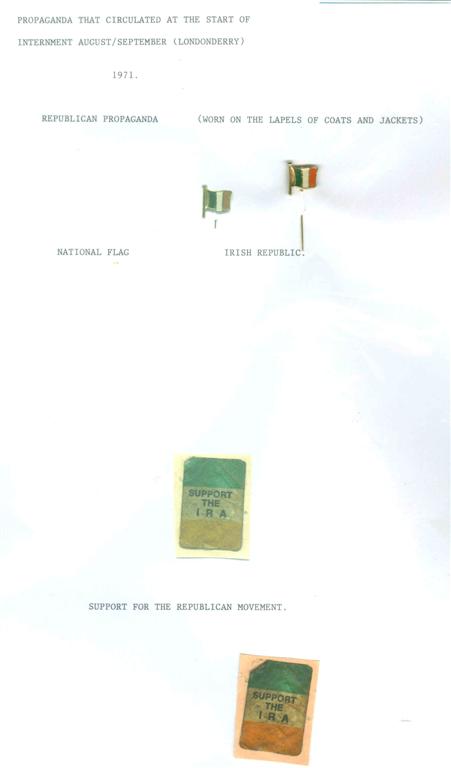

Collar badges popular for catching the fingers of searchers

The

entire UDR was ‘called out’ for full time service by the

GOC Northern Ireland for operations is support of the police

and army. We relished the prospect of being able to do

something constructive and we all felt we had a duty to leave

our jobs, don our uniforms and get on with soldiering to help

protect the decent law abiding citizens from the widespread

violence, which was practically out of control in many areas.

After

receiving a call from CSM John Kerr early that morning to get

my uniform on and get in as quickly as possible, I recall

arriving at our base in Macosquin to report for duty having

left work and family hurriedly and not knowing what was in

store. My mother quickly made me some sandwiches and a flask of

coffee and warned me to be careful as she stood watching me

leave. I knew she had tears her eyes. Naturally I assured her

that I would be fine and that she needn’t worry.

On

reaching Macosquin it was a classic case of ‘hurry up and

wait’. More men were arriving and there was a great deal of

speculation about where we were going and what we would be

doing. Then the OC arrived after having been at Battalion

Headquarters and got all the men to sit down in front of him

while he briefed us. There was no fuss or drama as he gave his

orders. We were then deployed 24 hours a day on a 12 hour shift

system for a variety of patrols, static guards and vehicle

check points over a continuous six week period.

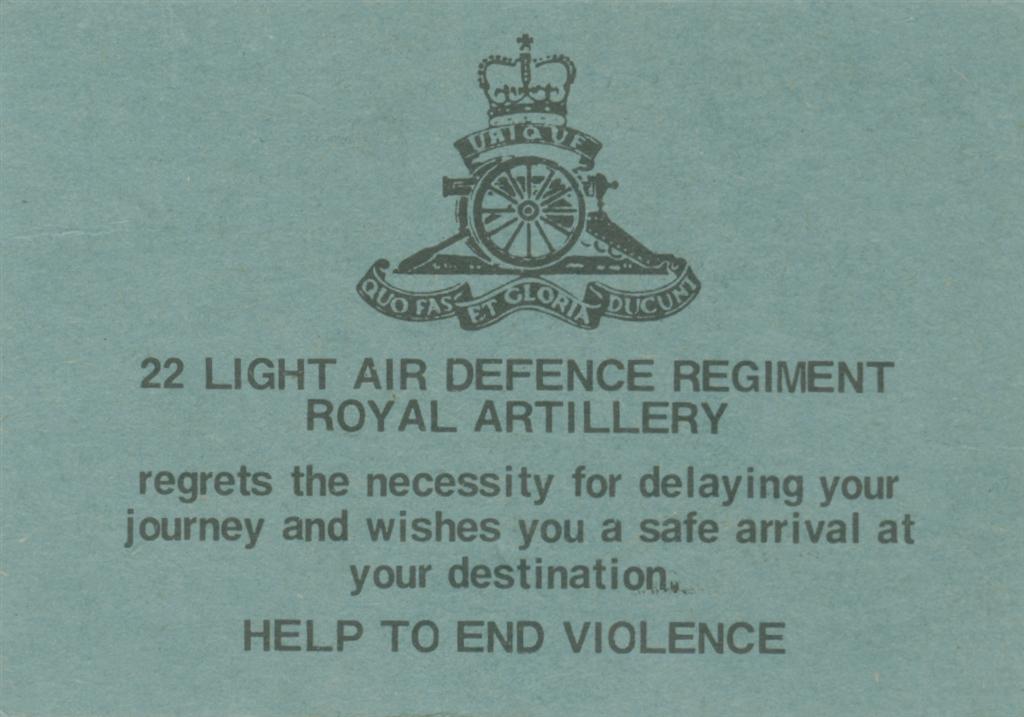

Our

operations were mostly based on the Border in the Londonderry

enclave and consisted of VCPs and some static guards including

guarding Magilligan Camp, which was to become an interrogation

centre for detainees. After the initial excitement and as we

settled down into a routine it became second nature to us as we

carried out our duties including travelling to and from the

various locations around Londonderry in support of 22 Regiment

RA.

Photo 25 CO 22 Regiment RA visiting E Company patrol in Londonderry City

Courtesy Cards

We

survived all weathers, even though it was August, in our olive

green combat gear and even more surprising we managed to live

‘in the field’ with very limited support from either

Company HQ or Battalion HQ. Many locals were quite friendly to

us and brought us goodies such as tea and cake or sandwiches.

These were a welcome change to the doubtful looking stew and

tea made with condensed milk sometimes delivered to us by the

CQMS. I remember being at Battalion HQ on one occasion when

huge containers of stew were being made inside a tent within

Ebrington Barracks and that confirmed my opinion that it was

indeed a doubtful delicacy. Some locals were decidedly

unfriendly to us and clearly resented our presence. Mostly, we

found that by being firm and as polite to them as possible made

them realise that we were not going to rise to their insults

and they eventually cooperated in a silent and sullen manner.

In

between visiting static guards, manning VCPs for long periods

and regular stints as Battalion Orderly Officer, usually for 12

hours at night, a duty which was even more demanding, I was

allowed to go home on a few occasions to wash, catch up on some

sleep and return to duty supposedly suitably refreshed.

Most of the soldiers did the same, as their hours on

duty were either day shift or night shift except on the odd

occasion when shifts extended to 18 hours or so. This happened

due the threat, sometimes the unavailability of transport for

relief or the routes that had to be taken because of rioting or

incidents in the city. There were few complaints if any about

the arduous conditions we endured, as this was what we had all

joined to do.

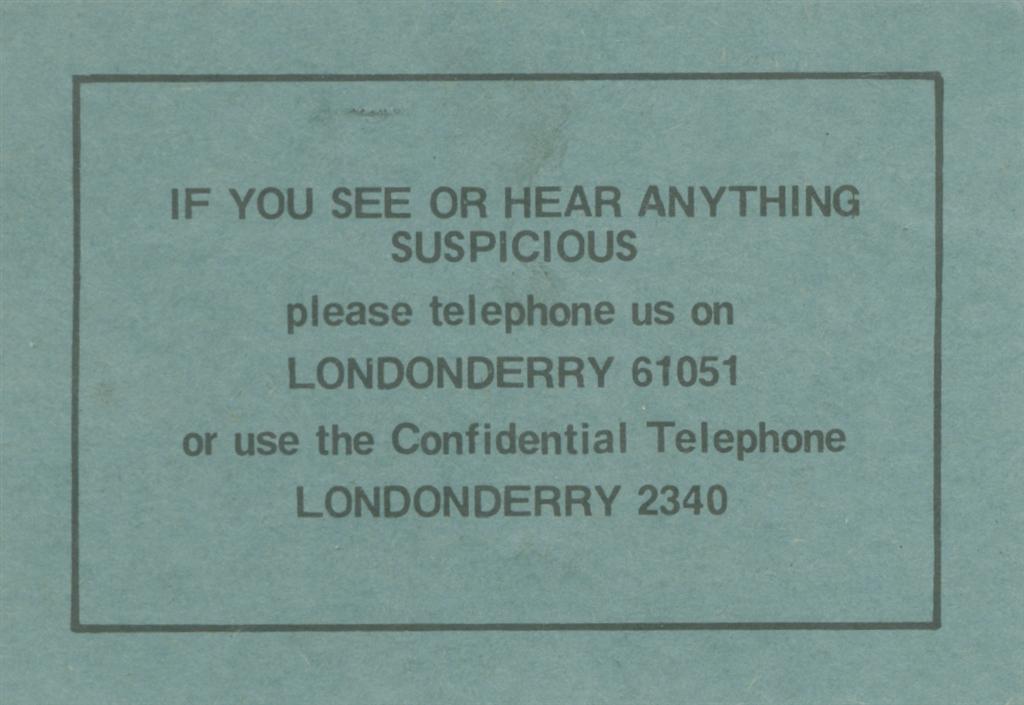

The Banned Book

One

sunny afternoon at Fanny Wylie’s Bridge Ballyarnett some of

our soldiers manning a checkpoint were fired on from a low

ridge about 300 meters away. Fire was returned and this caused

great excitement although no hits were claimed. Fortunately

there were no casualties amongst our men. When I arrived at the

scene a short time later one of the NCOs was holding a small

branch, which had been hit by incoming rounds and had fallen on

his head. This incident sharpened our minds beyond all doubt

that we needed to keep alert at all times and be prepared for

action.

Eventually

the ‘call out’ ended after six tough weeks and we returned

to our families, civilian jobs and the normal routine of

nighttime patrols and guards. We had all learned a lot and it

had been a real test of stamina and resolve. We had become an

even closer knit Company and a much more cohesive band of

‘brothers in arms’.

In

the aftermath of those days and weeks there was an enormous

increase in terrorist activity including the establishment of

No-Go areas. As the Official IRA faded gradually into relative

insignificance, the Provisional IRA became very well organised

throughout the Province and became a highly potent and

aggressive terrorist organisation. The ‘war’ began in

earnest. Even at that stage we thought it was not going to last

long.

How

wrong we were again” (Hamill, 2007).

Anti-Internment

Rallies

Magilligan

22 January 1972

An

Anti-Internment rally was held on Magilligan strand on 22

January 1972. A training day was being held at E Company

location on that day. This was cancelled and the company was

deployed on the periphery of the containment operation. The

Parachute Regiment were deployed on the front line and

successfully dispersed the crowds.

Londonderry

30 January 1972

That same month, on 30 January

1972, 20,000 people took part in a banned march in Londonderry

city. It was a protest against internment and had been

organized by the NICRA. The route towards Guildhall Square was

blocked by the Regular army at William Street. This channelled

the protesters into the Bogside where they assembled at

"Free Derry Corner".

The Regular army then carried out a cordon operation

that trapped the protesters on waste-ground between the Flats

and William Street. The troops were shot at on at least one

occasion before the Paras main assault on the rioters took

place. A Roman Catholic priest reported seeing a civilian

carrying a handgun during one of the shooting incidents. One

civilian was shot and died later before the Paras were deployed

(Doherty, 2007)

The Paras were ordered in to arrest rioters and as that

operation began they shot and fatally wounded thirteen known

civilians. That one incident alone accounted for more civilian

deaths than the persistently maligned B Specials had ever been

accused of in their 50 years of loyal service.

“One officer and 25 soldiers from E

Company were manning the Permanent Vehicle Check Point (PVCP)

on the Letterkenny Road that day. I was the radio operator and

as soon as the shooting started I monitored all the frequencies

in the city with my C42 radio to determine what was happening.

Despite the horror of the situation all the operators followed

proper radio procedure.

The PVCP was very busy when the shooting

stopped, in that many ambulances, including the Knights of

Malta passed through. Many people were injured and they were

treated in the Republic of Ireland.

One hour after the shooting stopped the area was very

quiet. There was no animosity from the people going through our

PVCP, which was strange. We were stood down by the resident

battalion at approximately 5pm and went for a meal in Ebrington

Barracks before returning home to Coleraine.

That incident was a turning point as far

as the security forces in Northern Ireland were concerned.

After the incident we had to upgrade our personal security and

patrol tactics in order to stay alive” S36.

Bloody

Sunday was followed by an upsurge in Republican violence. In the three years prior to

the incident six people were being killed each month. For

eleven months after the incident, forty people were killed each

month.

The Stormont devolved government was

suspended on 24 March 1972 by Edward Heath after

Brian Faulkner’s administration refused to transfer the

control of security in Northern Ireland to Westminster. From

that date a Secretary of State for Northern Ireland governed

Northern Ireland along with a team of junior ministers and

civil servants.

Official

IRA Ceasefire

Two

months later, after the terrorist murder of Ranger Best in

Londonderry, the Dublin based leadership of the Official IRA

called and maintained a ceasefire on the 29 May 1972.

Loyalist

No-Go Areas

The

following month, on Friday 30th June 1972, the

Ulster Defence Association (UDA) began to organise its own

'No-Go' areas. This action was a response to the continuation

of the Republican 'No-Go’ areas.

Then three weeks later it was another Bloody Friday in

Ireland’s bloody history. In Belfast on Friday afternoon 21st

July 1972 the IRA planted and exploded 26 bombs. In the space

of 75 minutes eleven people were killed (Bew & Gillespie,

1999) and 130 others were seriously injured. The whole recovery

operation in the aftermath of this terrorist attack was

confounded by a series of hoax warnings. This resulted in

delays in coping with the real bombs and the treatment of the

injured.

'Bloody

Friday' and the general revulsion with the carnage gave the

British Government the opportunity to deal resolutely with all

the ‘No-Go’ areas.

Operations

Motorman and CanCan

At

4am on 31 July 1972, 21,000 Regular troops moved into the

‘No-Go’ areas established in Londonderry in the aftermath

of internment protests of 1971. The Regular troops expected to

take heavy casualties if the Provisional IRA remained in

position. To that end the Province-wide operation to clear the

barricaded areas was known as Operation Motorman and was

preceded with a widely publicised ‘Sabre Rattling’ media

exercise. In 8

Brigades operational area, which included Londonderry city,

Operation Motorman was called Operation CanCan.

The general public fully expected the barricades to be

cleared but the date of the army’s deployment was withheld.

Operation Motorman succeeded in destroying the barricades with

minimal opposition and the area was secured by 7am.

That same day three car bombs planted by the South Derry

PIRA exploded without warning in the village of Claudy, killing

nine people, including nine-year-old Catherine Eakin. It has

been alleged that this terrorist atrocity was organised by a

Roman Catholic priest.

While the British government was planning Operation

Motorman they had other considerations to ponder. A British

government document dated July 1972 was released on 1 January

2003. This document explained for the British government the

possibility of redrawing the Northern Ireland border and

carrying out a transfer of the population.

“I was doing the searching on Op

Motorman for the Garvagh detachment. One day we stopped a car

with one occupant, the driver. He was French and did not speak

English very well. I lifted out the back seat and found a .303

Lee Enfield rifle. There were two rounds of ammunition, one

loaded and one attached to the rifle sling. We phoned the RUC

but they were too busy so a team or Royal Military Police came

out from HMS Sea Eagle and arrested this individual.

I had to go to HMS Sea Eagle later on and make

out my statement. It transpired that the Frenchman was going to

shoot an officer or at least a soldier if that was not

possible. He expected to be paid £200 for shooting an officer

and £100 for shooting a soldier. I was never called to give

evidence so I do not know how this finished up” S9.

“We

were called out for Operation Motorman and spent a long time on

a static VCP across from the back of Shantallow in Londonderry,

not far away from the Stokes travellers camp. That was an

interesting place. All the travellers had Republic of Ireland

documents, couldn’t write (supposedly) and signed with

variations of a cross” S47.

“During

Operation Motorman the Company was called out for full-time

duty for six weeks. That was from the beginning of August to

the middle of September in 1972. I spent most of the time on

the Derry border “dug in” trenches in a defended position

while operating a permanent checkpoint along with an Armoured

Reconnaissance Squadron from the Blues and Royals in support.

At

that time it was thought the Irish Army was going to invade and

take over Derry and we were there to defend against an invasion

force. It was seen as a full-scale war issue. I well remember

those nights of Operation Motorman, as there were soldiers who

didn’t want to be relieved from duty. They pleaded to stay

on, as they didn’t want to miss any of the action. That was

the sentiment of the time – time didn’t matter. We were

there to do a job. The pay was pitiful but the cause was

great” (Hamill, 2007).

The

Coleraine Town Bomb Blitz

The

following year, on 12 June 1973 Francis Campbell (70), Dinah

Campbell (72), Elizabeth Craigmile (76), Nan Davis (60), Robert

Scott (72) and Elizabeth Palmer (60) who were all Protestants,

were killed when a PIRA car bomb exploded outside the off

licence at the top of Railway Road in Coleraine.

Capitalising

on normal evacuation procedures, the PIRA had earlier exploded

a bomb at the car sales rooms in Hanover Place. This bomb

ensured that the town would be evacuated straight into the

second bomb in Railway Road; similar to the tactics used in the

IRA’s Bloody Friday atrocity.

Railway Road, the bomb was planted in the right foreground

One

of the many people who helped the injured and dying that day

was a WWII veteran called Frank Walls, a former Battery

Sergeant Major in the Coleraine Battery. He gave first aid to

many victims and organised stretcher teams using doors taken

from the bombed out buildings to move the victims to the

ambulances.

Photo

26 Frank, Mary and ‘Toots’ Walls, 1942

The

Sunningdale Agreement and the UWC Strike

The Sunningdale Agreement of December

1973 was a power sharing concept where Unionist and nationalists were persuaded to

work together and solve the political deadlock in Northern

Ireland. In response to the implementation of the Sunningdale

Agreement a Loyalist

ad hoc committee called the Ulster Workers Council (UWC) was

established. The UWC condemmed the Sunningdale Agreement and

conducted a two week General Strike starting on 15 May 1974.

The strike involved a combination of political,

paramilitary and popular support. Province wide the Loyalist paramilitaries used intimidation to enforce the strike. In

Coleraine town the ad hoc committee met in a Unionist

Councillor’s house. That committee was made up of councillors,

church ministers and trade Unionists who all gave ‘a nod and a wink’ to the paramilitary

leaders while discussing the blockade of the Coleraine roads.

This was a difficult time for E Company soldiers who had to run

the gauntlet of groups of ‘Loyalists’ on the River Bann

bridges. It was practically impossible to get petrol and

soldiers were allowed to buy Jerrycans of petrol from the Army

to enable them to travel to and from duty.

On 28 May

1974, in the second week of the strike, the power sharing

executive collapsed and direct rule was reintroduced.

After misjudging the attitudes of the Loyalist paramilitaries

during the UWC strike, Merlyn Rees, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland,

thought this was a good time to push Tom Nairn’s idea of

Ulster Nationalism. But the Loyalists wanted to maintain the Union . They were dissillusioned by

the inability of the Unionist politicians to capitalise on the power base presented to them

during the strike.

This strike proved to be the last time the Coleraine Loyalist

paramilitaries would fully co-operate with the Unionists.

Merlyn Rees and the Northern Ireland Office civil servants were

sowing the seeds of Ulster Nationalism on very stony ground.

Merlyn Rees visiting E Company Annual Camp at Ballykinlar 1974

The

Cell System

That same year, a series of

presentations on The Cell System were held throughout Northern Ireland.

Officers from the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) Co.

Londonderry command visited Coleraine and encouraged the local

UDA leaders to create secret terrorist groups of between four

to eight men who were prepared to conduct a clandestine murder

campaign against the IRA and their supporters. But sustained by

the success of the UWC strike the volunteers in Coleraine UDA

saw no value in breaking down their unit into smaller units.

It would be decades before the idea was finally adopted

by Loyalist paramilitaries such as the Ulster Freedom Fighters

and the Ulster Volunteer Force. The IRA did adopt the cell

system to a limited degree in 1977 to counter the covert

operations mounted against them by the security forces..

The

Coolkeeragh Power Station Raid

In

July 1975, E Company were tasked to guard Coolkeeragh power

station in Londonderry. That night intruders, who came in below

the perimeter fence, tied up the guard and stole six SLRs (Self

Loading Rifles).

A thorough investigation followed and it was found that

three of the platoon responsible for the guard duty that night

had Loyalist paramilitary connections.

The Coolkeeragh Guard Commander reported, “I was

fortunate or unfortunate to be in combat situations.

Once in Swatragh village there was a PIRA shooting

attack against our mobile patrols.

I am unable to recall any long-term pressure or stress

from these ‘contacts’, but there was one incident where my

patrol was held hostage in Coolkeeragh power station by a group

of armed Loyalist terrorists. That situation was more stressful

than the Swatragh incident. That was because the patrol was

being shot at in the Swatragh incident and your anti-ambush

drill training just kicks in. You know how to react to that

form of contact.

In the Coolkeragh situation we were being held by a

bunch of Loyalist terrorists and we had no control of the

situation. We could have been killed or injured and there was

nothing we could do. When I look back on that incident I know

that I prayed silently more that night than I have ever done

before or since.” S3.

John

Trussler

As

a measure of the calibre of the volunteers joining E Company,

consider the life history of John Trussler, who joined the

Company on 15 September 1975.

His military career started when he enrolled in the

Royal Artillery at Rhyl, North Wales on 5 January 1949. During

his gunnery career John has had postings to Borneo, Singapore,

Malta and BAOR (British Army of the Rhine).

He has been attached to 36th Heavy

Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Malta, 36th Guided Weapon

Rgt, 16th Light Air Defence (LAD), 102nd

Light Air Defence and 206 Light Air Defence Battery in

Coleraine. It was while serving with 102 LAD that he received

his first Royal Warrant on promotion to Sergeant Major PSI

(Warrant Officer 2nd Class Permanent Staff

Instructor).

On discharge from the Regular army he joined 206 LAD

Battery, Coleraine and received his second warrant as Sergeant

Major, Territorial Army Volunteer Reserve (TAVR).

On the 15 Sept 1975 John transferred to E Company as

Sergeant PSI and worked his way through the ranks again to

receive his third warrant as Sergeant Major. He was posted to

the Quartermaster’s Department in Battalion Headquarters and

later became the Training Warrant Officer of the Battalion

before retiring in 1982. John’s remarkable military career

has spanned 33 years.

Farrenlester

Road Explosion

“Four

Loyalist terrorists belonging to the UVF, Mark Dodd, Samuel Swanson,

Robert Freeman and Aubrey Reid

were killed in

a premature bomb explosion on the Farrenlester Road, near

Coleraine on 2 October 1975 when the

device they had been transporting blew up. I was in command of

the cordon on the Farrenlester Road between Coleraine town and

Macosquin village after the explosion” S10.

Long before the Farrenlester Road explosion the Rev

Brian Liddell had made a forthright statement from the pulpit

of 1st Coleraine Presbyterian Church in Coleraine.

He stated that he would never officiate at the funeral service

of any member of the congregation killed as a direct result of

their involvement in a terrorist act.

Rev Liddell did not conduct the funeral service for

Samuel Swanson. A

minister from another church was employed. The funeral

procession turned out to be the largest one that decade.

The

following Sunday, Rev Liddell reiterated his edict and went on

to say that any one who disagreed with his decision was free to

leave the church. Nobody left the church that day.

Search

Operation

The

following month, on the first Sunday in November, E Company

carried out a planned search of a wood near Dungiven. On the

search was an eager young Permanent Cadre soldier called Ronnie

Gamble. He had a habit of volunteering for such operations to

counter the dreary routine of Base Guard duties.

There were quite a few chuckles from others when the

soldier refused to take up the Mk 1 Prodder and instead

produced his personal electronic metal detector and started to

sweep the area designated to him. Within thirty minutes he

discovered expended cases close to a small reservoir, proving

that the area was used to test fire terrorist weapons.

The search intensified after that and E Company had two

more sets of finds that day including 140 assorted rounds of

ammunition, 30 ft of safety fuse and a tin of 93 commercial

detonators. This was one detailed example of many successful

search operations conducted by E Company. That was also the

month An Phoblacht presented an article on having Ulster

ethnically cleansed by the year 2000.

Opening

the New 5th (Co. Londonderry) Battalion Headquarters

Two

months later the Battalion Headquarters location was

transferred from Ebrington Barracks in Londonderry City to

Shackleton Barracks in Ballykelly. On 31 January 1976 Maj. Gen.

David Young presided at the official opening. He commented on

the Battalion strength being over 830 personnel including 62

female UDR with an average turnout of 250 soldiers every night

in County Londonderry.

The

Company Commander’s Daily Routine

“I

do not know how I managed to do it or how the other men managed

to cope with the workload. Most of the men were doing their

normal job during the day and reporting for duty several nights

every week and at weekends.

I was rising in the morning at 8am for breakfast. I then

called into the camp for a check on the situation with the

Company Sergeant Major and to pick up my mail. I then went off

to school. Sometimes I called into the camp at 1pm. After

school I was usually home for 5pm and immediately went to

sleep. My wife would wake me at 6pm for dinner and by 7:30pm I

would be back in the base.

At 8pm the patrols would be briefed and then head out on

patrol. Sometimes I would accompany the patrol. On other

occasions I would have to go to either Londonderry or

Ballykelly to attend an Operational Briefing (O Group) with all

the other senior officers. I would be back home in bed for 4am,

hopefully!

How I was capable of carrying out this punishing routine

for twelve years without a major health problem is beyond me.

In 1976 I was promoted and E Company changed command. I then

had a series of senior staff postings and retired at the age of

58 in 1982. The first six and a half years were terrible for

both my family and myself. After that, the next five and a half

years were not so bad.

From 1970 until 1976, we had progressed from a small

group of ex-servicemen and a few green recruits to a large

strong company, ready, capable and willing to serve anywhere.

It was a privilege to be part of it. You felt that you were

really needed – you did not always know the importance of the

job you were doing. Your men did not know what car bombs your

roadblocks had prevented.

On one occasion I can remember our roadblock obviously

stopped ‘something’. The car approaching us did a hand

brake turn. It was hard to tell your men you didn’t know

exactly what they were achieving. But they were doing a good

job in deterring the terrorist. We even caught some of them in

the commission of their evil crime. My motivation was always

loyalty to the Crown. I enjoyed service life, the atmosphere of

the Officers’ and Sergeants’ Mess and working with the

men” S1.

Change

of Company Commander

“I

took over command of E Company in July 1976 and concentrated on

improving recruit training and training for operations while

maintaining and strengthening all our operational commitments.

We had no difficulty in attracting new male recruits together

with ‘Greenfinches’ (female soldiers) and the Company grew

rapidly in size and strength. The age profile of the company

changed considerably in the late 70s and we had many more new

young men and women joining. This new influx provided

additional challenges and required much effort to ensure we

were operationally ready at all times. With the Detachment at

Garvagh the Company had a total strength of over 250 – almost

half a Regular army Battalion” (Hamill, 2007).

Photo

27 Major Victor Hamill

Police

Primacy

The

policy document ‘The Way Ahead’ was introduced in July 1976

and implemented in 1977. It discussed the Ulsterisation of

security in the Province, where the RUC were to take the lead

and the UDR replaced the regular army to provide patrol

operations throughout most of the Province.

The policy of Police Primacy led to many changes in the

Northern Ireland security scene. The full-time soldiers became

known as Permanent Cadre and their pay increased to be on

parity with the Regular army pay scales. There was also an

increase in recruiting and training in order to cope with the

ever-expanding patrol areas. The Tactical Area of

Responsibility (TAOR) of the UDR in all areas increased as the

Regular army was withdrawn and the Permanent Cadre took over

their patrol areas.

The full-time soldier sometimes worked in excess of

eighty hours each week. These figures were massaged in that

full-time Company Commanders stopped the clock when the patrols

were relieved on the ground. That deleted the time it took for

you to get back to base, return your equipment and get home.

This reduced your operational hours by five hours on some

duties.

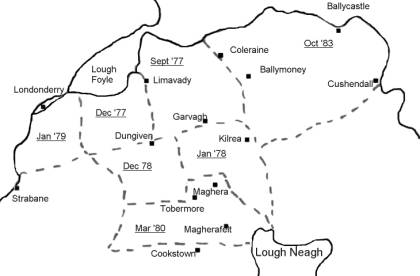

Map

1 The Expanding TAOR

Alongside this overt change in tactics there was also an

increase in covert tactics where all terrorist suspects became

subject to more intense surveillance. The part-time element

also experienced many changes.

”Our

operations became more sophisticated and patrolling became much

more efficient and effective. As time went on the UDR developed

a closer working relationship with the RUC and joint patrols

became standard procedure.

The UDR input to supporting the RUC had a clear

advantage because of local ‘nouse’. There were exceptions

of course when frictions surfaced due to personality

differences on rare occasions or when the military approach

differed to the policing requirements. Any of these perceived

or real problems were always successfully overcome by

discussion or negotiation and by applying common sense and

decency.

Patrol tasks became our bread and butter as well as

guards and other duties and we became proficient in advanced

skills at section, platoon and company level. We operated

‘Framework Operations’ – mutually supporting patrols that

basically saturated an area and kept the terrorist guessing.

These were very successful tactics in preventing ambushes of

patrols and the free movement of terrorists and their

munitions” (Hamill, 2007).

Not only was there a radical change in Security Force

tactics, there was an equally radical change in Republican

terrorist tactics after the short IRA ceasefire ended in 1975.

In 1976/77 twenty-nine UDR personnel and thirty-seven RUC were

murdered. This rate was double that from the previous three

years. Eleven of the murdered UDR personnel were from 5 UDR

alone.

Increased

Terrorist Activity in 1976

E

Company soldiers managed to survive one of those murderous

attacks. At the start of August 1976, 21 Platoon had a close

call on Portballantrae Rifle Range in County Antrim. A milk

churn bomb was buried at one of the firing points and a

pressure plate was hidden on top of it so that anyone standing

on the firing point would detonate the bomb below.

“At

the start of the range day Sergeant George Mitchell and I were

making our way down to the butts for the first detail of the

March and Shoot firing practice. Corporal Robert McCarron and

another soldier were setting out six rounds of ammunition on

each firing point. Various teams were out on a forced march

that culminated in a competition shooting practice. When the

March and Shoot team arrived on the firing point they had to

charge their magazines with the ammunition and then engage the

targets.

Photo

28 Sgt George Mitchell

Sergeant

Mitchell and myself were about fifty metres from the firing

point when this blast came. It was like a heavy wind and we

felt this blast on the back of our legs. I looked round and saw

Corporal McCarron flying through the air. A soldier was lying

in the trench in front of the firing point screaming with his

face covered in blood.

As we ran back to the firing point Alex was already on

the scene supervising the first aid to the two injured

soldiers. He did a wonderful job under the circumstances.

Although the Private soldier looked the worst of the two

injured, all his wounds were superficial. Corporal McCarron had

sustained severe chest and jaw injuries. The surgeon at

Coleraine Hospital had to use pioneering techniques to

reconstruct Corporal McCarron’s jaw.

Corporal McCarron had stepped on the pressure pad. He

survived this Republican booby trap attack but was unfit for

service” (H Jamieson, 2007).

The

Republican onslaught continued and within a week of the

Portballintrae attack the commercial heart of Portrush town was

under attack.

“A

Republican terrorist arson bomb attack took place in Portrush

on Tuesday 6 August 1976.

This remains the top north coast resort and the ten-bomb

attack was designed to coincide with the peak of the holiday

season. We were on cordon duty all through the night and were

also tasked to search the town for unexploded IED’s” S10.

The following week on the 12 August 1976 E

Company were responsible for manning the PVCPs on the Muff,

Buncrana and Letterkenny roads as well as the checkpoint on the

Quayside. This was part of the Company’s contribution to the

Emergency Call Out of the UDR Province wide. It allowed the

Resident Battalion to monitor the crowds at the Apprentice Boys

parade in Londonderry city.

The Province and 5 UDR in particular suffered from

brutal attacks carried out by Republican terrorists from 1976

onwards. In March 1977 there was an emergency call out of UDR

personnel for a two-week period in order to curb the Republican

murder spree. The SDLP spokesperson on law and order protested

in the local press claiming that the call out was unwise.

The Unionist politicians called on the Government to

deal more effectively with the IRA and also reintroduce

majority rule.

They also set about organising a second Province wide

strike. One of the organizers was the Rev Ian Paisley and the

group was known as the United Unionist Action Council (UUAC).

That strike ran from Tuesday 3 May until Friday 13 May in 1977

and it proved to be an abject failure. This time there was no

general uprising of the Unionist and Loyalist family. The

Coleraine paramilitaries were not prepared to support political

leaders who, they believed, failed to capitalise on the

advantages they had gained for them in the 1974 UWC strike.

Despite threatening to resign if the second strike

failed Paisley carried on. A subsequent ‘show of force’ by

the DUP degenerated into the donning of cherry berets, climbing

a hill in a nice safe area and the waving of firearms

certificates at the invited media.

Visit

by the Queen August 1977 (Her Silver Jubilee Year)

Three

months later the Company was called out again for the Queen’s

visit on 10 and 11 of August 1977. E Company was tasked to

secure the coastline between Portstewart and Portrush,

particularly the area overlook in the anchorage of the Royal

Yacht Britannia. The Company Tactical Headquarters was

established in Portrush Town Hall. Twenty-one Platoon was based

in the harbour and used the Harbour Master’s office as a

Platoon Headquarters. Twenty-two and 23 Platoons patrolled

Portrush town and Garvagh detachment, 24 Platoon, provided

patrols on the town boundaries. The Company had the unique

responsibility of coordinating the deployment of over 400 men

and women from different army units in that security operation.

“At 4am on 11 August I decided to take a foot patrol

from Company Headquarters to the West Strand to ‘freshen

up’ for a visit by the Commanding Officer and the Brigade

Commander at 6am. We had no swimming gear for a dip in the sea

and as far as I know we were undetected. The Commanding Officer

and Brigade Commander thought we were very alert when they

arrived” (Hamill, 2007).

It was a sunny day when the Royal Yacht Britannia

and the escort ship arrived and anchored off the NW coast at

Portrush. There was a carnival atmosphere in the town. Two

local fishermen, Derek McLeister and Freddy Fleming set up a

barbeque in the harbour close to 21 Platoon Headquarters.

They barbequed fresh mackerel all day and the platoon

was well fed.

The Royal Marines patrolled the harbour area in their

fast patrol boats all day and occasionally called into the

harbour to enjoy pints of Guinness and beer as well as the

adulation of young boys and girls. Unfortunately E Company did

not have the same glamour but the general public did give them

a friendly pat on the back now and then for a job well done.

The security threat was minimal and the IRA seemed to have

boycotted the occasion.

Later on, the Queen visited the University of Ulster.

The SDLP boycotted the Coleraine visit. After her visit a bomb

exploded in the grounds of the University. In a follow-up

operation an army explosives search dog indicated an interest

in two different rooms of the University.

The

Killings after 1978

From

1978 onwards the ‘Ulsterisation’ of Northern Ireland

security did not result in more Ulster deaths but instead it

led to a spectacular reduction in some of the death rates. The

yearly average for civilians (117) and the Regular army (39)

dropped to forty-six and thirteen respectively. After 1991 the

killings dropped further to twenty-six and 2.5

Despite the upsurge in the murder of UDR/RUC personnel

in 1976/77 table 2 shows how this changed in 1978 to nine and

twelve respectively and finally dropped in 1991 to one and

three.

Table

2 Murder Victims Yearly Average

|

Phase |

Civilian |

Reg

Army |

UDR |

RUC |

|

1969

- 1977 |

117 |

39 |

11 |

12 |

|

1978

- 1990 |

46 |

13 |

9 |

12 |

|

1991

- 2001 |

26 |

2.5 |

1 |

3 |

When

the terrorist killings are attributed to their respective

groups they are also quite revealing. Table 3 shows that up

until 1977 the Republican terrorists were killing 96 people

every year and the Loyalists 48. After 1977 this figure dropped

to 60 and 12 respectively.

Table

3 The Terrorist Yearly Murder Rate

|

Phase |

Republicans |

Loyalists |

|

1969-1977 |

96 |

48 |

|

1978-1990 |

60 |

12 |

|

1991-2001 |

18 |

18 |

This

can be explained in part by the fact that Republican terrorists

had adopted the cell system in 1977 to counter the covert

operations mounted against them by the security forces. As well

as that the sectarian killers now had more political direction.

This helped to reduce the civilian deaths as the killers were

ordered to concentrate on the security forces. Despite this

political control of the Republican campaign the sectarian

atrocities did continue as the gunmen countered the Loyalist

murders with more ‘spectaculars’.

The drop in Loyalist murders can be related to the drop

in Republican murders so there were fewer ‘tit-for-tat’

attacks on Roman Catholics. At the same time the Intelligence

services had infiltrated all Loyalist groupings and

deliberately slowed down their kill rate. The Loyalist groups

at this stage were now more corrupt and were focused on

extortion, drug dealing and protection rackets. Then in 1991

the terrorists were on parity, each group murdering 18 people

every year.

Previous

Chapter 7 - Prelude

to Terrorism

Next

Chapter 9 - E

Company - The Middle Years - the 80s