Previous Chapter 6 - The First Officer Commanding E Company Next Chapter 8 - E Company - The Early Years - The 70s

Chapter

7 – Establishing E Company 5th (Co Londonderry)

Battalion, The Ulster Defence Regiment

Prelude

to Terrorism

There

were two phases of civil dissent preceding the 1970–2005

Loyalist and Republican terrorist campaigns. The first phase

involved a short-lived civil rights campaign. This was followed

by a series of left-wing confrontations and then the terrorist

campaign started.

The first phase can be traced back to 1962, just after the

failure of the last IRA murder and sabotage campaign known as

Operation Harvest (1956–1962). The IRA leadership reappraised

their strategy and moved from murder and sabotage campaigns to

political action. This led to elements of the IRA attending a

planning conference in August 1966, which then led to the

formation of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA)

on 9 Apri1967.

Those attending that first conference included Cathal

Goulding, who was the Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army

(IRA), (Coogan, p 482), several protest group leaders and various

politicians. The IRA as an organisation was dormant at this time

but there were Republicans involved who believed that the

non-sectarian civil rights movement could be used to ‘subvert

Unionist power in Northern Ireland’ (Smith, p81).

In order to influence civil and human rights reforms in

Northern Ireland the NICRA adopted the non-confrontational

methods used by Dr Martin Luther King Jr in the USA during the

early 60s. Both Protestants and to a greater degree Roman

Catholics in Northern Ireland had genuine grievances and both

communities stood to benefit from any such reforms.

The first protest march in August 1968 was a peaceful

event. It contained a good cross section of Northern society with

university students, Roman Catholics, Protestants, left-wing

militants and IRA activists all enjoying the day out. By August

1968, the peaceful protests and the singing of ‘We Shall

Overcome’ were antagonizing more and more Protestants. Many

viewed the song as threatening rather than a Roman Catholic

desire to overcome institutionalised discrimination. Paisleyite

and Unionist groups started to organise counter demonstrations.

This in turn led to the banning of many protest marches and an

increase in sectarian conflict.

By October 1968 the second phase of the descent into

terrorism started. The objectives, composition and the approach

of the NICRA protests started to change. The non-sectarian ethos

disappeared and the protests became more provocative. This new

radical approach appeared to be more influenced by the French

student riots of the 60s than the Dr Martin Luther King Jr

protests. Within the next two years many of the reforms such as

the disarming of the RUC were lost when sectarian violence

undermined the civil rights campaign to a degree where civil

rights and Irish nationalism united.

The civil rights demands then became nothing more than a

smokescreen behind which left-wing activists and Republicans

pursued the destruction of the state of Northern Ireland through

confrontation. This confrontational approach would evolve over

the next thirty years into the Adams Republican ‘cutting

edge’ philosophy (O’Doherty, p98). Confrontations and

terrorist attacks were used to promote Republican propaganda and

to remind the world ‘that there is an unresolved problem to be

dealt with’ in Ireland.

During these early protests the policing problems were

compounded by Unionist politicians who ignored the opinions of

senior RUC officers (Doherty, p76) Political interference

constantly forced the RUC, the Ulster Special Constabulary and

the army on some occasions to confront the sustained and

coordinated civil disobedience campaign with inappropriate and

repressive tactics. This destructive Unionist interference

continued until Direct Rule was implemented in 1972.

Then on New Years Day 1969, the left wing students group

called People’s Democracy (PD) organized their infamous march

from Belfast to Londonderry via Burntollet Bridge. This march

proved to be as contentious as the

‘Love Ulster’ parade planned for Dublin in 2006. The

belligerence of the ‘marchers’ was apparent from the

beginning, as many were later found guilty of assault when they

kicked their RUC escort party to the ground and trespassed onto

the Overend Farm in Bellaghy. The RUC are often accused of

failing to protect the ‘marchers’ at Burntollet but the

Bellaghy assault proved that they were under strength and

incapable of dealing with serious incidents.

As expected the 1969 coat trailing affront through many

Protestant areas with tricolours flying created many bloody

confrontations. During the follow-up riots in Londonderry city

several phone calls went out from the left wing agitators

requesting supporters to start similar confrontations throughout

the province. (Wallace, 1969). This tactic was designed to

stretch the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) beyond their capacity

to cope. The tactic worked and in August 1969 troops were sent to

Northern Ireland to support the exhausted RUC. The stage was now

set for the third phase, the 1970–2005 terrorist campaign.

The Provisional IRA formally established itself on 11

January 1970 (Smith, p83). This was followed in July the same

year by the inaugural meeting of the Woodvale Defence Association

(Wood, p1). Many other Loyalist organisations went on to raise

similar defence units throughout Northern Ireland.

The murder of Northern Ireland citizens by these self

appointed guardians escalated in 1971 and by the year 2001 the

Republican terrorists had murdered 863 Protestants and 408 Roman

Catholics. The Loyalist terrorists murdered 197 Protestants and

704 Roman Catholics (wesleyjohnston.com. 2007). Compared to the

Republican terrorists, the Loyalist terrorists had a relatively

minor role in the murdering of the real guardians of the Northern

Ireland community. To their tally they added the lives of three

UDR soldiers as well as the first and the last policemen to be

killed in the current murder campaign, Constables Arbuckle and

O’Reilly.

Perfidy

The

major deceit exercised by the Republican and Loyalist terrorists

was that of perfidy. That act is defined as wrongful deception or

as the Concise Oxford Dictionary defines it, a deliberate

“breach of faith, treachery”. For all the security forces of

Northern Ireland, perfidy was the major problem. Under Article 37

of the Geneva Convention the act of feigning civilian,

non-combatant status is prohibited.

The ‘Heroes of Ulster’ and ‘Irish Freedom

Fighters’ declared war and always broke the Geneva Convention

by not dressing in the soldiers uniform. Take the typical example

of the midnight murders of Constables Armstrong and McLean on 11th

April 1987 in Portrush. On that date two Republican terrorists

exercised their murderous skills on the RUC for the 240th

time by firing handguns into the backs of the Constables heads.

All the terrorists fought a dirty war that did not require

direct confrontation or holding the ground for extended periods.

The attacks made on E Company in County Londonderry included the

murder of off duty soldiers in front of their families that

sometimes included the murder of their children, Loyalist

infiltration of base locations, the use of car bombs, roadside

and culvert bombs as well as ‘shoot and scoot’ attacks

against the back of vehicle patrols and foot patrols.

Despite the blatant disregard for international rules of

warfare the Republican and Loyalist terrorists caught and

convicted were always claiming that they were not ordinary

criminals but political prisoners or even prisoners of war.

Recruiting

for the Ulster Defence Regiment

In

November 1969, one month after Major George Lapsley had retired

from the Coleraine Battery (Territorial Army) as Battery

Commander an army officer friend from England wrote to him asking

him to join a new army unit being formed in Northern Ireland to

replace the B Specials. It was to be called the Ulster Defence

Regiment (UDR).

George travelled over 900 miles within the next four

months recruiting all over the Province. On one occasion he swore

in a group of volunteers from the Bogside, all Roman Catholics.

Let there be no doubt that even in those dark times there were

many brave people in Republican and Loyalist terrorist controlled

areas prepared to serve their community until they were either

murdered or intimidated out. Take for example the Royal

Enniskilling Fusilier veteran Bobby Boyd. He originally came from

the Creggan and joined the Regiment in those early days. He was

still serving in 5 UDR when Republican gunmen murdered him at his

front door in 1985.

The

Role of the Ulster Defence Regiment

On

the last day of March 1970 the B Specials were stood down and

replaced by the Ulster Defence Regiment. The mendacious tactics

used by nationalist politicians to denigrate the B Specials were

then applied relentlessly on the UDR for the next three decades.

The UDR was known as the largest infantry regiment in the

British Army but it also met all the criteria of a militia. It

was a locally raised unit of volunteers who were tasked to defend

their immediate area and population from internal dissent. It

contained part-time, full-time, male and female volunteers who

resolutely faced terrorism for the benefit of the whole community

of Northern Ireland for the next three decades.

The

initial role of the Regiment was defined in the Battalion

Standing Operational Procedures (SOPs) as, “to support the

Regular Forces in Northern Ireland, should circumstances so

require, in protecting The Border and The State against armed

attack and sabotage”.

The method of fulfilling that role was always

restricted to:

-

Guard duties at key points and installations.

-

Foot, airborne, sea borne and vehicle patrols and search operations.

-

Establishing checkpoints and roadblocks.

Regimental

Structure

Just

like the Militias raised one hundred years before, each Battalion

of the UDR was responsible for a specific area of the Province

with at least one Battalion in each county. The Battalion was

sub-divided into a Battalion Headquarters base and a number of

Companies of 100 men. Each were spread throughout the Battalion

area with their own base locations.

For

the first year of the establishment Lieutenant Colonel Davidson,

an ex-B Specials veteran, commanded 5 UDR.

After that, the command structure of 5 UDR was always

similar to that used in many Colonial defence forces. Posting a

locally born officer to a role senior to that of Company

Commander did not happen too often. Some talented officers did

receive figurehead postings as Colonels or else were given Staff

Officers jobs at Regimental Headquarters or Brigade HQ for a few

years before retiring.

With

rare exceptions, the Battalion was always under the Command of a

Regular Army Commanding Officer (CO). The Battalion

Second-In-Command was usually the most senior part-time officer

and this prevailed until 1991 when the post was designated to a

Regular officer, usually the Training Major. The Quartermasters

Department were normally under the command of a Regular Army

Officer. The Senior Non Commissioned Officer (SNCO) posts of

Communications, Chief Clerk, Intelligence Cell, Armourer and the

Regimental Sergeant Major

(RSM) were always filled by the Regular Army personnel on a

two-year posting.

“This

was always a prime area for successful working relationships or

otherwise depending on how Officers and SNCOs got on with the

various Commanding Officers and other ‘blow ins’ and vice

versa.

Usually we were fortunate to have career minded and highly

motivated Commanding Officers, Training Majors (TISOs),

Quartermasters (QMs) and RSMs over the years who introduced new

and better operational procedures and higher training standards

while there were a few who managed to make little impact on our

war with the terrorists.

Some of the Commanding Officers tried to ‘reinvent the

wheel’ and there were times when the Company commanders and the

Battalion Second-in-Command had to use their influence to ensure

‘new’ tactics worked. Lt. Cpl. Hugh Tarver was one of the few

Commanding Officers who went out on patrol with the part-time

soldiers at night. He usually sat in the back of a Landrover and

joined in any task allocated by the Patrol Commander. There were

many occasions when he stayed out on patrol until 4am and was at

his desk in Battalion Headquarters again at 8.30am” (Hamill,

2007).

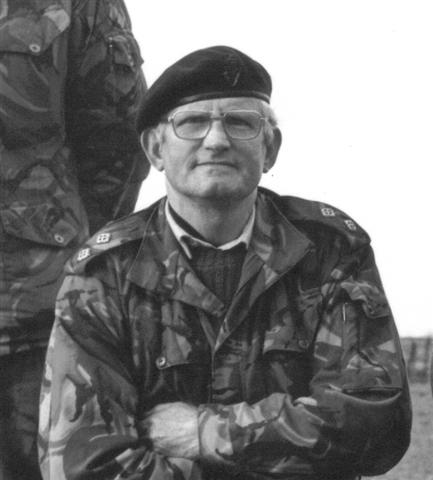

Photo 16 Lt Col Hugh Tarver

There

are two possible reasons for the limited career prospects of the

local officers. The first could be labelled ‘The Application of

The O’Neill Principle’. Before the Plantation it proved

detrimental for the English to train and promote the native born

Hugh O’Neill to a position where he was able to compromise the

political and operational control of the native militias in 1590.

Second, there were no individuals from Co. Londonderry with the

necessary credentials or commitment to fill the more senior

posts.

Base

Locations

The 5th (Co Londonderry) Battalion of the UDR

had a HQ base in Ebrington Barracks, Londonderry City. The

Battalion was made up eventually of seven companies. Two of the

companies were located in Londonderry city. These were, A Company

on the West Bank, B Company in the Waterside, C Company at

Claudy, D Company at Shackleton Barracks in Ballykelly, E Company

at Laurel Hill House, Coleraine, F Company in Magherafelt and G

Company in Maghera. These companies opened, moved or closed down

on the whim of the ever-evolving recruiting figures and

operational requirements.

From its inception the Regiment

required full-time soldiers for administration duties and to

guard the Battalion and Company HQ bases throughout the day. The

full-time soldiers were called Conrate, referring to the fact

that they were paid consolidated rates of pay, a similar pay

scale used for the Permanent Staff soldiers employed in the TA

Centres (Potter, p39). After 1977 the Conrate were referred to as

Permanent Cadre (PC).

The

part-time element did not operate until after normal industrial

and commercial working hours and the week ends. The UDR, although

part of the Regular Army, was classed as a Home Service Regiment

and all other army units posted over to Northern

Ireland were known as Regular units and

were staffed and manned by Regular officers and soldiers.

Formation

of E Company 5 UDR

Photo 17 Major George Lapsley

After

the initial recruiting phase George Lapsley was given the task of

forming the company to be based at Coleraine. One of the officers

sent over from England to form the Regiment was Brigadier Logan

Scott – Bowden, Commander UDR. Staff from Headquarters Northern

Ireland (HQNI), Lisburn, conducted the actual vetting and

recruiting. The HQNI staff were responsible for losing many good

recruits particularly in the Coleraine area. Take for example,

the Sub-District Commandant of the Aghadowey B Specials.

Although he was a bit old, he had the command and respect

of all the men in the Aghadowey area. He was informed that he was

too old and would be unable to ‘hack it’. But the recruiter

was talking indirectly to all the B men and they all thought that

if the government didn’t want their Commandant they would not

get any of them.

Another ex-B Special Commandant, Jimmy Simpson, managed to

get into the Company despite his age. That was why Coleraine had

so many B men in the Company in those early years.

Photo18 Jimmy Simpson

In

the initial stages of forming the Coleraine Company just over

forty men were recruited. One of the first problems facing the

new company was the fact that there was no armoury in Coleraine.

The nearest armoury was located in Ballymoney at the North Irish

Horse base in John Street, which by then had become B Company 1

UDR. Because of this the Coleraine volunteers had to travel to

Ballymoney to report for duty.

The

Part-Time and Full-Time soldiers of E Company were drawn from every

walk of life. They included, architects and accountants, company

directors and plumbers, labourers, bank staff and the occasional

undercover operative from the various intelligence units.

Sometimes bosses as private soldiers were under the command of

their staff who were Corporals or Sergeants. There were

volunteers from both the Roman Catholic community and the

Protestant community, some had King Billy tattoos and others had

Tricolour tattoos. Despite the convolutions in civilian status,

religious conviction, political orientation, ethnic origin and

army rank the company merged into a cohesive working unit and

carried out their duties in an impartial manner.

Company

Structure

Each

company contained a Company HQ with a Major in command and a

staff consisting of a civilian Pay Clerk, an Administration

Warrant Officer (AWO), a Permanent Staff Instructor (PSI, usually

a Colour Sergeant), a Company Sergeant Major (CSM), a Company

Quartermaster Sergeant (CQMS), a Guard Commander (Sergeant) and a

Base Guard of ten soldiers, a civilian storeman and a Motor

Transport Corporal in charge of maintenance.

The main body of soldiers were in the three platoons of 28

men each with an officer (Platoon Commander) and a sergeant

(Platoon Sergeant) in overall command. The platoons were

sub-divided into three sections of at least eight men each with a

Corporal and a Lance Corporal in command. For patrol operations

the sections were split into two teams (or ‘Bricks’) of four.

Women were recruited into the UDR in 1973 and these female

soldiers were usually attached to the platoons or staffed the

company Operations Room.

E Company contained four Part-Time platoons and generally

speaking, each platoon drew its members from specific areas of

Coleraine town as outlined in Table 1.

The majority of 21 Platoon were volunteers from the

Portrush and Portstewart (The Ports) and the Windyhall areas.

Volunteers from the east side of the Bann manned 22 Platoon and

23 Platoon was known as The Heights Platoon. Garvagh and the

surrounding areas was the main source for the platoon located in

Garvagh RUC station, 24 Platoon.

Twenty-three and 24 Platoons were usually tasked to work

together when required and the other two platoons also operated

together when required.

Table

1 Company Structure

|

Regimental

HQ Lisburn |

|||

|

5th

Battalion HQ (Londonderry) |

|||

|

‘E’

Company HQ (Coleraine) |

|||

|

21

Platoon The

Ports |

22

Platoon East

Bann |

23

Platoon West

Bann |

24

Platoon Garvagh |

|

No1

Section No2

Section No3

Section |

No1

Section No2

Section No3

Section |

No1

Section No2

Section No3

Section |

No1

Section No2

Section No3

Section |

Dress

and Equipment

“Everything

seemed strange at the beginning; being sworn in, being issued

with your kit (which usually didn’t fit) and learning what to

do with various items of kit, such as the poncho, puttees and

webbing, not to mention those terrible looking berets! Finally,

being issued with a .303 rifle and ammunition, which you took

home with you when off duty because we didn’t have an armoury

in those days. The rifle, ammunition and the rifle bolts were all

hidden in different places in your home until you were going back

on duty” S Brownlow.

Catering

“When

we reported for duty we travelled with our uniforms and weapons

and usually carried a small pack with a flask of tea or coffee

and sandwiches or bread and jam. Sometimes we shared with men who

had no personal rations with them and sometimes we were lucky to

have rations issued from Battalion Headquarters via the Company

Quartermaster Sergeant (CQMS).

I recall watery stew was often on the menu and by the time

it reached us it was invariably cold but we usually ate it along

with dry bread. This was followed by rice pudding and jam washed

down with a mug of sweet tea. Conditions were primitive in the

extreme during the first couple of years but improved greatly in

later years as the standards rose.

It was always very good to go on joint operations with the

troops stationed at Kilrea or Londonderry as not only did we

contribute to the tasks but also we enjoyed ‘egg banjos’ and

other tasty snacks after patrols” (Hamill, 2007).

Ballymoney

Company Transfers

“I

was one of the 50 or so men who transferred from B Company of the

1st (Co Antrim) Battalion based in Ballymoney to the 5th

(Co Londonderry) Battalion in late 1970. The aim was to form a

new Company based initially at Macosquin, a few miles outside

Coleraine. As we had already been deployed on operations in

County Antrim and Belfast, we were keen to get on with the tasks

in our new operational area, which included Londonderry City and

County.

This was an important change, as we believed the

Londonderry border with County Donegal in the Republic of Ireland

would become part of our new territory and so it was to be.

We

also wanted to get to know our new Battalion, which had its

Headquarters in Londonderry at the former naval base, HMS Sea

Eagle at Ebrington Barracks (1840)” (Hamill, 2007).

The

Macosquin Base

“Eventually

common sense prevailed and in 1971 the Company was relocated at

the former B Specials’ Drill Hall of the Englishtown Platoon in

Macosquin. This had been purpose built in 1966/67. It had a

reinforced roof and there was a .22 range at one end of the hall.

It was very bare and spartan and totally different from

the facilities and organisation we had become familiar with in

Ballymoney. There were no offices, stores, armoury, sangars or

guardroom, just a few chairs in an empty building with a

five-barred gate outside at the entrance, and so we quickly got

on with the job of making this building our new Company

Headquarters.

This was pioneering soldiering at its best and we all felt

determined to work well with our new Company Commander, Major

George Lapsley who quickly recognised our strengths and

weaknesses, the old and bold, and the experienced, dedicated

soldiers who were keen to make their mark.

Initially, I suspect the locals in Macosquin were somewhat

intrigued and bemused at the Army’s comings and goings in their

sleepy village community but soon accepted our presence. It was

to become a very busy place as the pace of our operations

increased and various essential improvement works were carried

out. Before long we had a suite of Portacabins for offices and

the base became more military like and fit for purpose”(Hamill,

2007).

Company

Duties

The

duties and operational tasking were planned at Battalion HQ.

After that the OC E Company was expected to task his men to cover

these duties. A couple of weeks before the start of a new month

he would sit down in front of his table and read out the duties

to the four platoon sergeants. They had the loyalty of the men in

their platoons. The OC would say, “Red 2, next Monday night”.

That was a duty requiring twelve men. One of the Platoon

Commanders would put their hand up. Next the OC would call out

for the Power station, the Telephone exchange and other places

that were under threat. Hands would go up for each duty. Then the

Platoon Sergeants would go and detail off the men to cover that

particular duty.

Eventually the Company strength was large enough to parade

a Company Headquarters, four full platoons and a Base Guard. At

that stage a coded duty sheet was issued to every man in the

Company so that they knew when to parade for duty. The company

was able to carry out duties on every night of the week as well

as the weekends.

“The

first operational tasks we had at Macosquin were foot patrols in

the Macosquin area. We had no transport to move us around so we

carried out Lurk patrols. That was a tactic where we would go out

on foot patrol and stay hidden in the hedgerow, stopping the

occasional car, just as we had done in the ‘B’ Specials. Many

months later we did get our own vehicles. Prior to that we had to

borrow our transport from other army units when we wanted to

expand our patrol base. Usually we managed to borrow two soft-top

Landrovers and a 4-ton truck. Thanks to the generosity of all the

local Army units.” S11.

“The

company was also responsible for guarding the Bushtown

electricity sub-station and other static key installations in the

immediate area. After Bloody Sunday when the terrorism escalated

we also went on to guard RUC stations, including Kilrea RUC

station. In later years we carried out guard duties at places

further afield including Coolkeeragh power station near

Londonderry city” S11.

Pay

Days

The

Company was at Macosquin for one year before moving to Laurel

Hill House in Coleraine. On one occasion at Macosquin the Army

had run out of ready cash and was unable to send us our weekly

pay. George Lapsley went and explained the problem to a local

businessman. The man trusted George implicitly and allowed him to

draw £400 from his safe. The next day the Commanding Officer of

the Battalion went out of his way to visit the businessman and

thank him because he could not believe that he had allowed George

to go into his safe and help himself.

The

Company Sergeant-Major

While

the Company was at Macosquin it was growing in strength and

needed a good Company Sergeant Major (CSM). A Company can’t

function efficiently without the guiding hand of an experienced

CSM.

Photo 19 Sergeant Major John Kerr MBE MM

Sergeant

Major John Kerr MBE MM

The

OC first met John when he went to Garvagh to seek his help in

forming the new E Company. He had heard from various sources

about John’s military career and other work John had done in

the past. After talking to him for a couple of minutes the

Officer Commanding knew that he was the man for that challenging

task. John Kerr was one of the finest men you would ever meet. He

had a presence and men under his gaze knew to obey instantly. But

in their hearts they all knew they had a dependable friend as

well.

At that time John worked for TBF Thompson in Garvagh. When

TBF learned that John was about to depart he immediately offered

him an inducement of £20 a week.

That was a very substantial pay rise in the early 1970s.

But John had given his word and, in truth, he was looking forward

to a return to army life.

In the Sergeant’s mess men would listen enthralled as he

talked about his experiences on the Anzio landings in 1944. On

one occasion he was nearly shot by the German officer who

captured him. John rebuked a young sergeant for expressing a

‘Gung Ho’ attitude towards dealing with terrorists. John

looked the unfortunate Sergeant in the eyes and asked, “Have

you ever killed anyone? It’s not a nice experience you know”.

He continued, “One particular day at Anzio I was bayonet

charging across a farm yard and the Germans counter charged us. I

pulled the trigger on my rifle and a young German soldier fell to

his knees in front of me. He was about the same age as me, 18

years old. He looked at me and he knew he was dying. I knew he

was dying. I ran on and we won that day”.

That story appears in Fitzgerald’s (1949) ‘History of

the Irish Guards in the Second World War’. The book outlines

the last battle of the 1st Battalion Irish Guards at

Carroceto on 6 Feb 1944. Page 308 describes why John was awarded

the Military Medal:

“Guardsman

English, a Bren gunner and Guardsman Kerr, like terriers after

rats, shot and bayoneted their way through every stable and up

into the lofts”.

What

this version failed to convey was the haunted look on John

Kerr’s face as he told his story to a very chastened young

Sergeant.

Many of the senior officers who visited Laurel Hill were

surprised to meet the man who had trained them years before at

the Officer Training School, Warminster.

John

only had one week’s holiday a year; he always went to Annual

camp. That was the time when John and his Merry Band: Albert,

Hugh and Kitty would enjoy life in relative safety, sometimes

commandeering the Company Commander’s vehicle as their taxi.

His ashes now rest in Coleraine Cemetery and you can be sure he

often looks across the river Bann towards Laurel Hill.

Photo

20 Albert McAfee

Photo 21 Hugh

McQuilken

Photo 22 Kitty McConachy

Laurel

Hill House

It

was not until 1972 that the Coleraine Company was based in

Coleraine town. Up until that time George Lapsley was second in

command of the 5th Battalion (Co. Londonderry) UDR. He

requested and was granted the post of Company Commander E Company

(Coleraine) and was then addressed as the OC E Company.

As the OC E Company George Lapsley was not happy with the

former USC Drill Hall in Macosquin. He spent a lot of his limited

time travelling around the Coleraine area looking for a suitable

base location for his Company. He eventually met Mr Noel Henry

who bewailed the fact that his planning permission to use Laurel

Hill House as a hotel had been turned down. The agreed price

between George and Noel was £24,000.

Laurel Hill House

The Army Property Services department were suspicious as

to how George could get the property for such a low price. They

did not have to wait long to find out. Because of a combination

of wet and dry rot it took over £100,000 to repair the house and

then more to convert it for the Company’s use.

Laurel Hill House is located on the high ground to the

west of the town. It overlooks the River Bann and was an imposing

gentleman’s residence with extensive grounds. The Kyle family

inhabited the house since 1711; hence the road outside the estate

was named Kyle’s Brae. The last Kyle to own it was Henry, the

son of Rev Arthur Kyle, the minister of First Coleraine

Presbyterian Church from 1761 to 1808. Henry died in 1878.

During WW2 Laurel Hill House accommodated elements of the

American army. Recent renovations unearthed a detailed map of

Europe on the wall of the former Sergeants’ Mess. This drawing

outlined the progress of the Allied Forces in Europe during WWII.

The map has been carefully preserved.

The

Pink Lady

The

house was supposed to be haunted by the ghost of the ‘Pink

Lady’ and several brave souls swore they saw her in the early

morning hours. But that was usually after some social occasion.

On one occasion the company mascot, a Great Dane called Swain,

was taken into the house but as soon as it reached the bottom of

the stairs, its hackles went up and it refused to climb the

stairs. That story only embellished the legend. There were some

soldiers on guard duty from time to time that refused to enter

the house after midnight!

The

Renovations

The

house and grounds required much renovation to convert to a Rifle

Company base and during the initial months while the necessary

work was underway the company had to make do with quite a few

hardships in accommodation and facilities but it was much better

than Macosquin.

The accommodation was not custom built but it was made

very accommodating and comfortable. In the outbuildings the Round

Tower became the Guard Room and Armoury while the adjacent shed

and yard space was ideal for the Motor Transport (MT) Section

where the MT Lance Corporal soon established his workshop and

office. The cow byres beside the MT were cleared out and

transformed into a 25-metre mini-range.

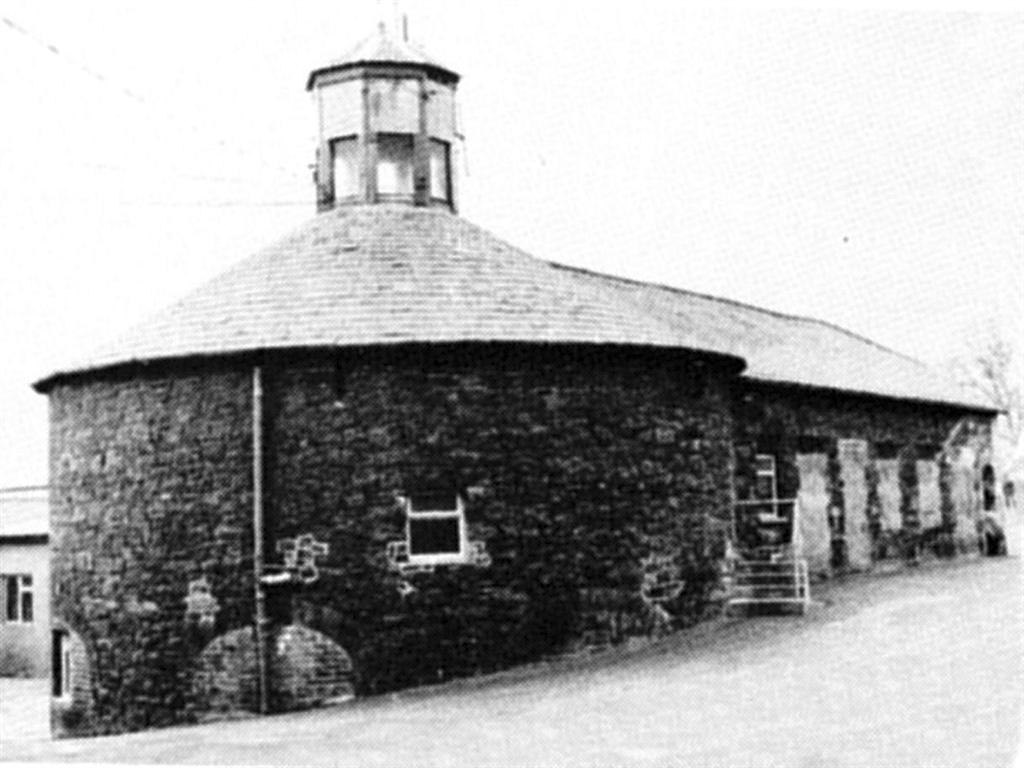

Photo 23 The Guard Room

In the main house the first floor contained the Warrant

Officers and Sergeant’s Mess, a lecture room, the Company

Sergeant Major’s office, Company stores and the Training office

for the Permanent Staff Instructors.

Upstairs there was space for the Junior Ranks’ Bar and

the Officers’ Mess and the Pay Clerks office while the Company

Commander’s office looked out over Sandleford Bridge. The

original Company Operations Room was also on the first floor.

Various other improvements were carried out on a number of

occasions to improve the gate sangars and perimeter fence

including building a Pipe Range where the tennis court had once

been. A snooker room was established below the Guardroom and this

was put to good use on many occasions.

“The

Junior Ranks Bar was open about three nights every week and after

a training day. It was a great place to relax and have a drink

without having to worry about your personal security. Unlike

public bars, there was discipline built in and no fights or

serious confrontations ever took place.

To liven the nights up our platoon commander organised a

live band. There was Jimmy McCluney on the accordion and Scrapper

O’Neill on the drums along with the four of us who were in a

local band. The craic was always good, particularly on a

Thursday night. That was the Company night when the whole of the

administration block was open for training, stores issues and

exchanges, administration and discipline. After the

administration was sorted everyone retired to the bar and

relaxed” S20.

“The

rule was that if your platoon was on duty that night, the duty

platoon was denied use of the bar facilities. The platoon duty

came first. On one memorable night a particular sergeant took it

upon himself to relax in the Sergeants Mess as opposed to

patrolling with his platoon. I took over the OC’s office and

had the offending Sergeant marched in. I gave him a severe

‘talking to’ and reminded him about the basic ground rule and

not to repeat his indiscretion. I carried on and completed my

paperwork before proceeding to Ballykelly to take command of my

platoon from the Battalion Operations Room. There was a knock on

the office door and in popped the Sergeant’s wife. She was in

tears and complained about the way I had spoken to her poor

husband for not reporting for duty” (H Jamieson, 2007).

“A

helipad was built within the grounds and before long helicopters

were landing and taking off much to the delight and surprise of

the neighbouring residents and their children who peered through

the fence in amazement. Eventually a drill hall was built beside

the helipad. The drill hall was fitted with a bar facility and on

many occasions each platoon held their own social functions

there, including children’s Christmas parties.

All in all the company now had a Headquarters, which had

character, and purpose and everyone was very proud of the

facilities at Laurel Hill House” (Hamill, 2007).

The Company Sergeant Major

When

the company became established in Coleraine town, WO2 J Kerr MBE

MM was appointed Administration Warrant Officer (AWO) of the

Company and the duty of Company Sergeant Major (CSM) passed on to

a series of part time SNCOs including the late Roy Marshall. He

had served in the Enniskilling Fusiliers from his teenage years

and had seen much action around the world, including Kenya,

Cyprus, and Kuwait.

Photo 24 CSM Roy Marshall

The

Base Guard

Once

the company was located at Laurel Hill House, a Base Guard had to

be established. The Full-Time soldiers employed on the base guard

at Coleraine were still referred to as Conrate. The two Base

Guard sections worked on a weekly rota. One week they would cover

three, sixteen-hour shifts and the following week they would

cover four, twelve-hour shifts. Full-Time soldiers through the

day did this from 4am until 8pm.

Guard Commander-Sgt Gordon Taylor

The Part-Time soldiers covered the Base Guard at night and

some of the weekend duties. The Full-Time soldiers usually worked

a forty-eight-hour week. The Full-Time soldier’s pay was very

poor at this time and the rota gave them the opportunity to earn

money in civilian work.

Later on in the 80s the Part-Time soldiers were allowed to

do the base guard at Coleraine. This allowed the Permanent Cadre

soldiers to go on leave or courses.

Building new gate sangars became the subject of much

debate. Many ‘expert’ opinions were presented and dismissed

but it was usually the Royal Engineers who had the last say.

One day the Guard Commander was tasked to cut down one of

the trees in the yard. The tree was hollow but it came down

without any problems. The next task for the Guard Commander that

day was to collect all the confidential documents and incinerate

them. We did not have a proper incinerator at that time so the

Corporal decided to use the hollow tree as an incinerator.

He piled in all the documents and sprinkled the pile with

a bottle of petrol from one of the Landrovers. Then he asked me

for a box of matches to light the papers. It was a windy day and

he had a bit of trouble starting the fire. He then went into the

hollow and tried again despite all my warnings.

The

petrol fumes went off with ‘whoosh’, his beret came flying

through the air and then the Corporal emerged from the tree

hollow with his face burnt red, his glasses and eyebrows gone.

E

Company Strength

“Within

six months the 40 Volunteers from the Ballymoney camp became 100

men then 200 and then 289 men and 9 officers by the time I

retired.

Females

(Greenfinches) were then recruited into the UDR in 1973. They did

an excellent job alongside the men out on patrol and in the

bases.

We had one of the best companies in the whole of the UDR

– it was showcased and we won many competitions and were

visited by many VIPs. There has always been a great notion of

service and volunteer spirit in Coleraine. There were many Royal

Air Force, Royal Navy, Army and ex-B Specials and there was great

respect for all these men – they were looked up to” (Hamill,

2007).

“Our

operational capability progressed and increased as the terrorist

threat grew. It was quite normal for most part-time soldiers to

carry out a minimum of three operational duties per week with

training fitted in at weekends. Much emphasis was placed on

weapon training and shooting and we spent many training days and

nights at Magilligan, Portballintrae and Eglinton ranges.

Other infantry skills for counter terrorist operations

were practised too and we took it all in our stride as we knew

the situation in the Province was deteriorating fast. The

atmosphere was terribly exciting and demanding – there was a

camaraderie that I had never experienced; the comradeship was

infectious.

There was a real “can do” attitude and a determination

to make the Regiment, the Battalion and the Company a success.

There was strong motivation to raise the professional standard

and to do the best we could. Men volunteered readily for all

operational tasks and there was never a problem in filling the

duty roster. Platoon Commanders organised and practised call-out

procedures. Section Commanders and Platoon Non-Commissioned

Officers became more responsible for commanding guards and

patrols and it was very satisfying to see the command structure

working as the Company continued to grow in strength and

capability”(Hamill, 2007).

Frank

Pancott

“Frank

Pancott was quite a character. He had served in the regular army

in WW2 with quite a distinguished career. He had been a Permanent

Staff Instructor with the B Specials and eventually found himself

in the post as store man to E Company 5 UDR. In the course of his

duties as store man he had to attend conferences with the

Quartermaster (QM) of 5 UDR.

At one of these conferences there was a long and heated

discussion about losses. Frank never had any losses; in fact I

thought Frank had surpluses. No losses were ever recorded while

Frank maintained the stores at E Company ‘and my lips are

sealed’.

As well as the store men attending this conference there

were other QMs from other units. One QM had lost a Parka Jacket.

These were valuable ‘starred items’ and had to be accounted

for throughout their service. It was frowned upon if you ever

lost one of these items. On this occasion the QM was being told

off for incurring the loss. Another QM thought this was hilarious

and started laughing. The Commanding Officer turned to him and

said, “What are you laughing at? I will be with you in a minute

because I want to know what happened to the boat which appears to

have gone missing from your account” S4.

Previous Chapter 6 - The First Officer Commanding E Company Next Chapter 8 - E Company - The Early Years - The 70s